Kristeen Irigoyen- Hernandez aka Lady2Soothe Follow @OurVoicesEcho

On December 7, 1941, Japanese planes attacked the United States Naval Base at Pearl Harbor External, Hawaii Territory, killing more than 2,300 Americans. The U.S.S. Arizona was completely destroyed and the U.S.S. Oklahoma capsized. A total of twelve ships sank or were beached in the attack and nine additional vessels were damaged. More than 160 aircraft were destroyed and more than 150 others damaged.

July 26, 1940, 4 months prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor President Roosevelt, with the intention of continuing to grant licenses froze all Japanese assets and ended trade by prohibiting the exportation of oil products preventing Japan whose dependency on the US for most of their crude oil and refined petroleum were ordered to depart from US harbors without loading or unloading cargo. In a confidential 26 page memo dated December 4, 1941 headlined “Methods of Operation and Points of Attack.” and “Japanese intelligence and propaganda in the United States” FDR chose to dismiss the red flags warning war was imminent. “In anticipation of possible open conflict with this country, Japan is vigorously utilizing every available agency to secure military, naval and commercial information, paying particular attention to the West Coast, the Panama Canal and the Territory of Hawaii”.

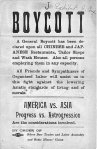

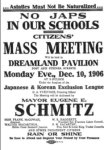

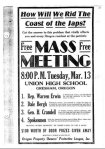

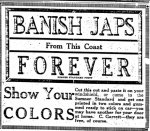

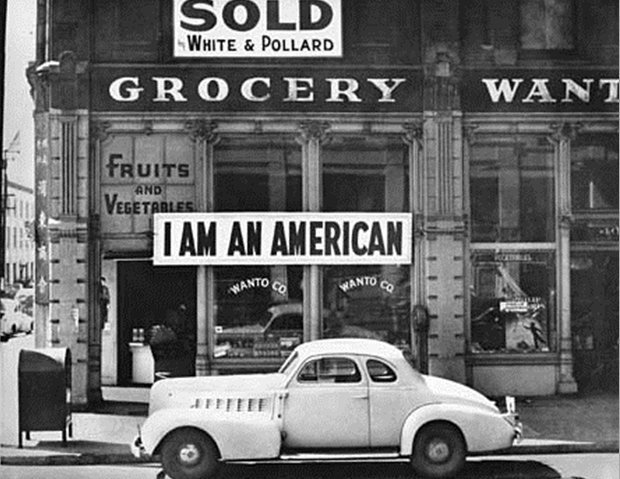

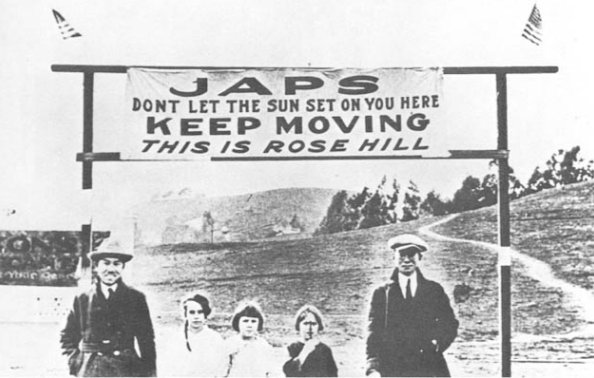

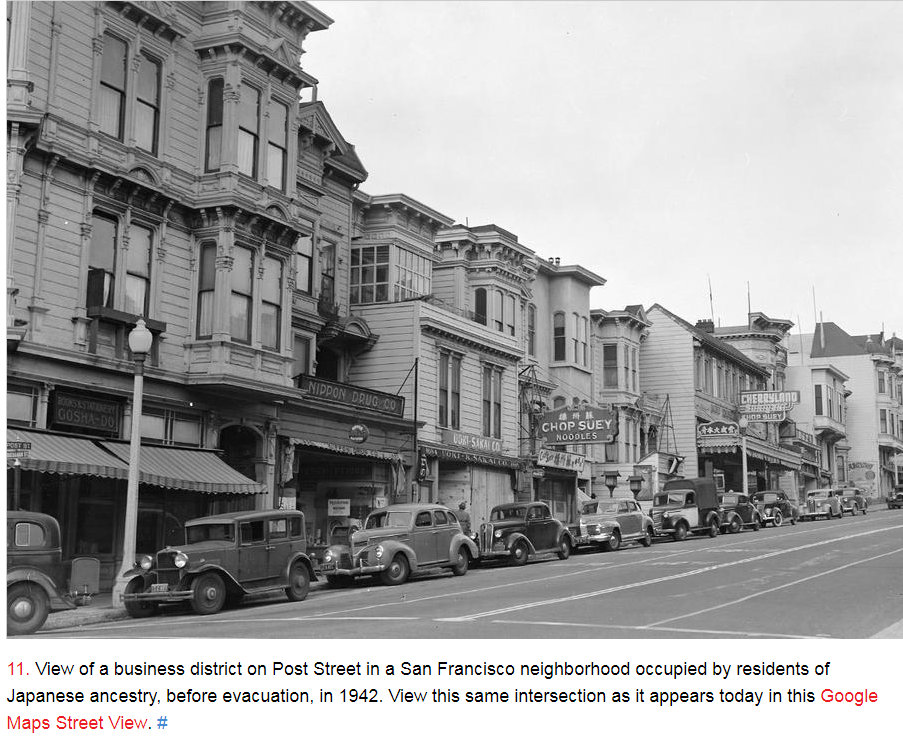

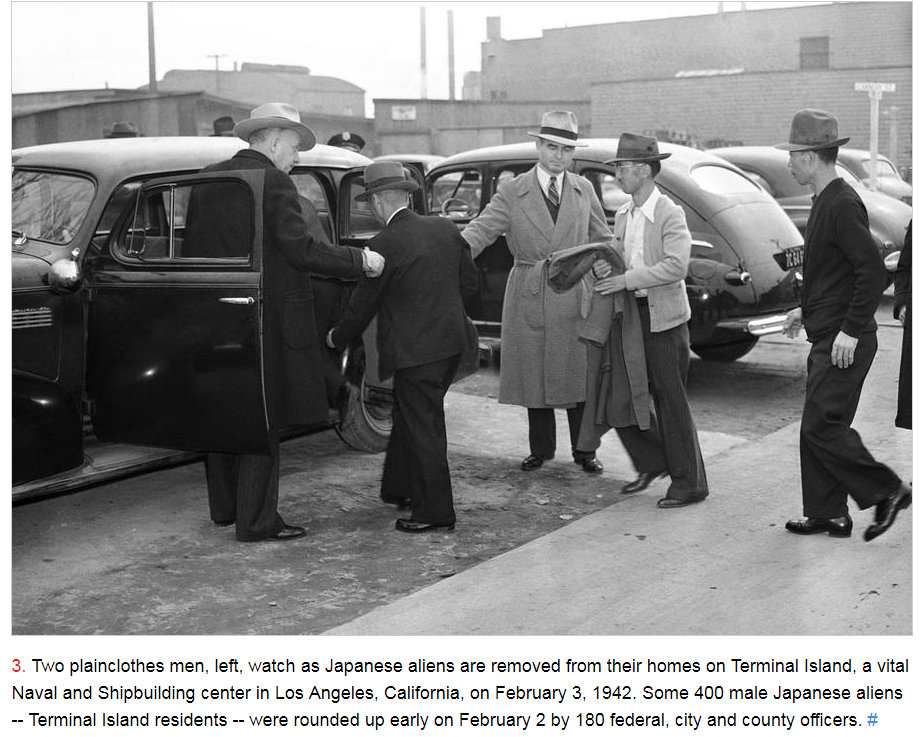

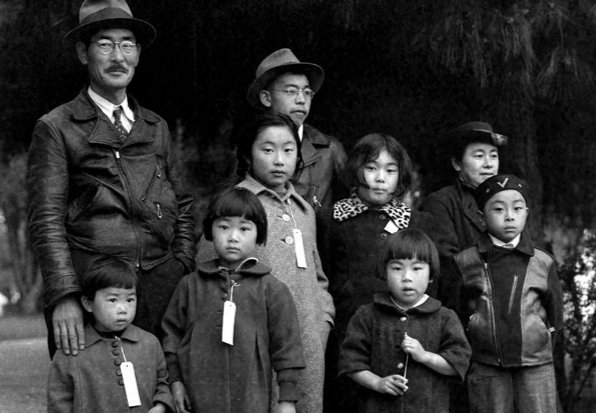

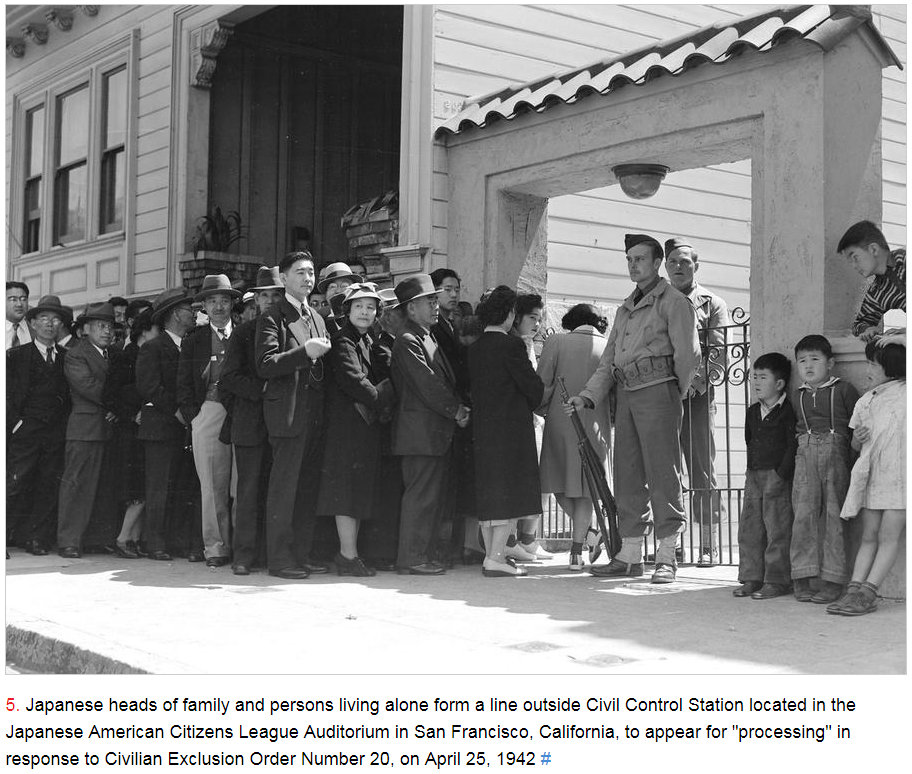

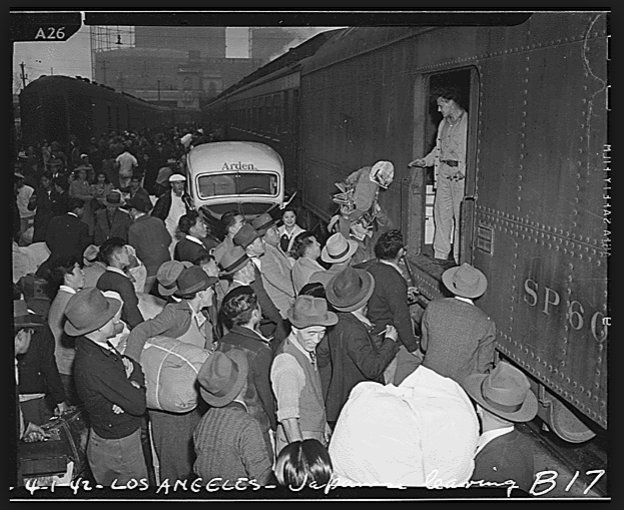

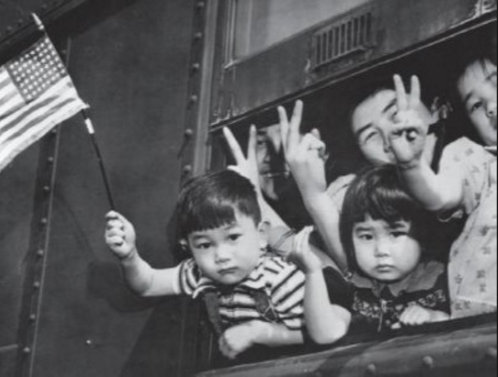

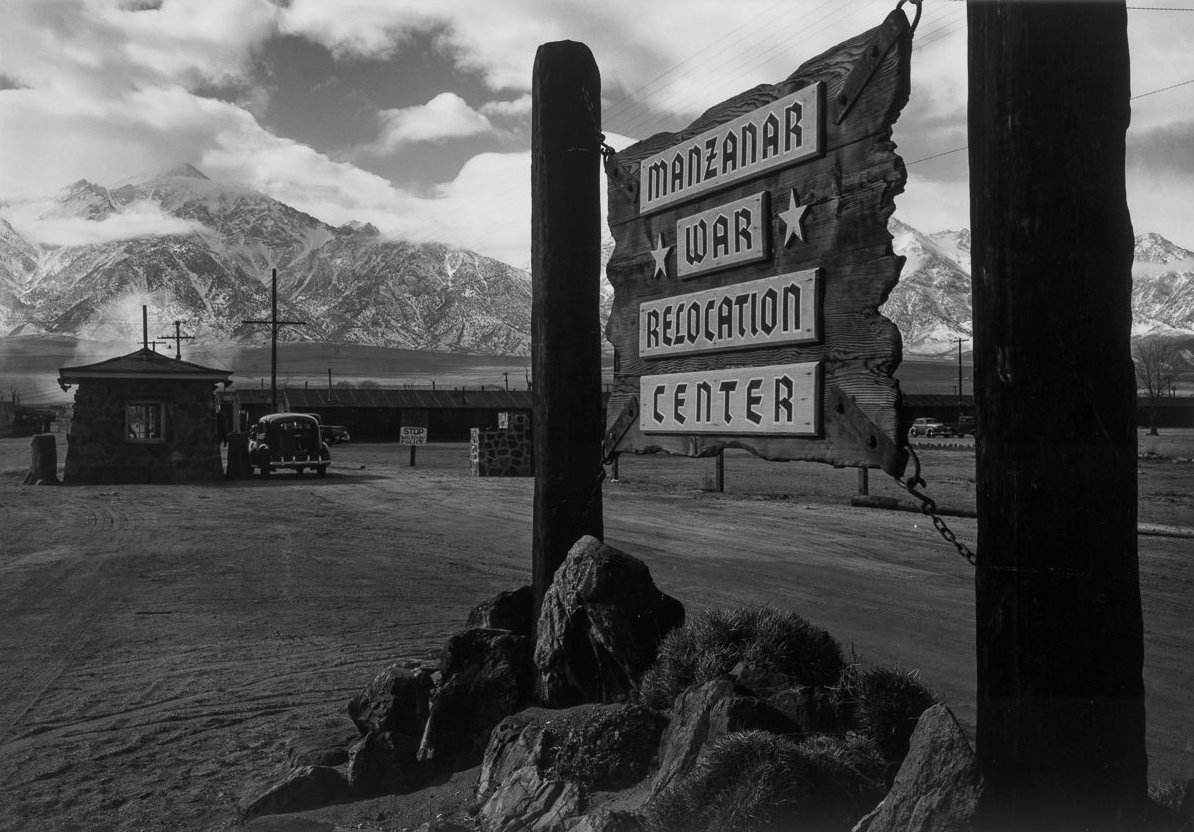

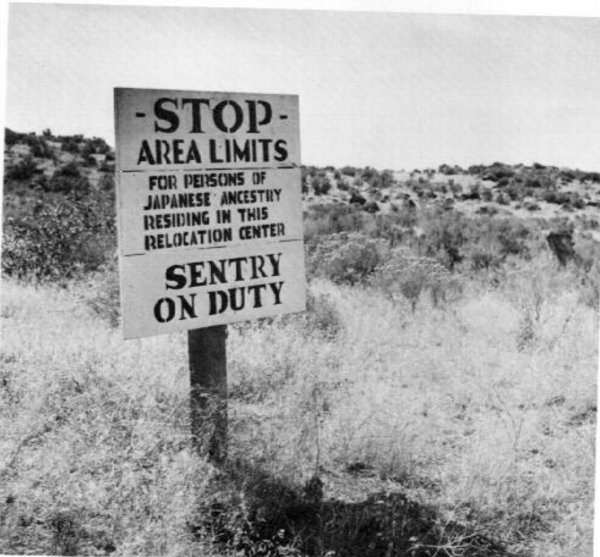

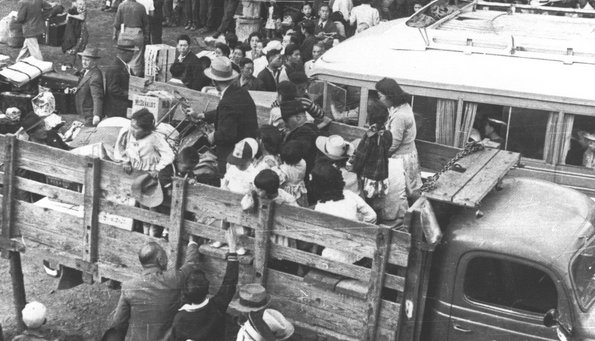

Yellow Peril Racism began to envelop the country; where at first the Japanese had been welcomed as cheap labor they now became criminals and terrorists and by Feb. 1942 Americans of Japanese ethnicity suspected of having even one drop of Japanese blood were ordered to Relocation Camps. The little Japanese girl who taught my father to write his name in kindergarten was sent to Manzanar and never seen or heard from again.

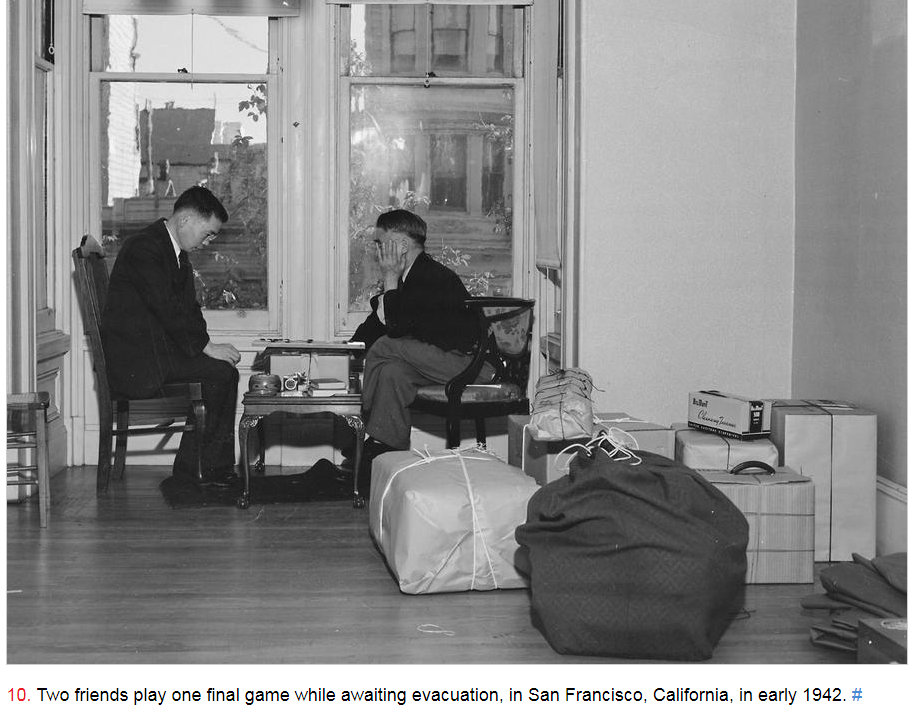

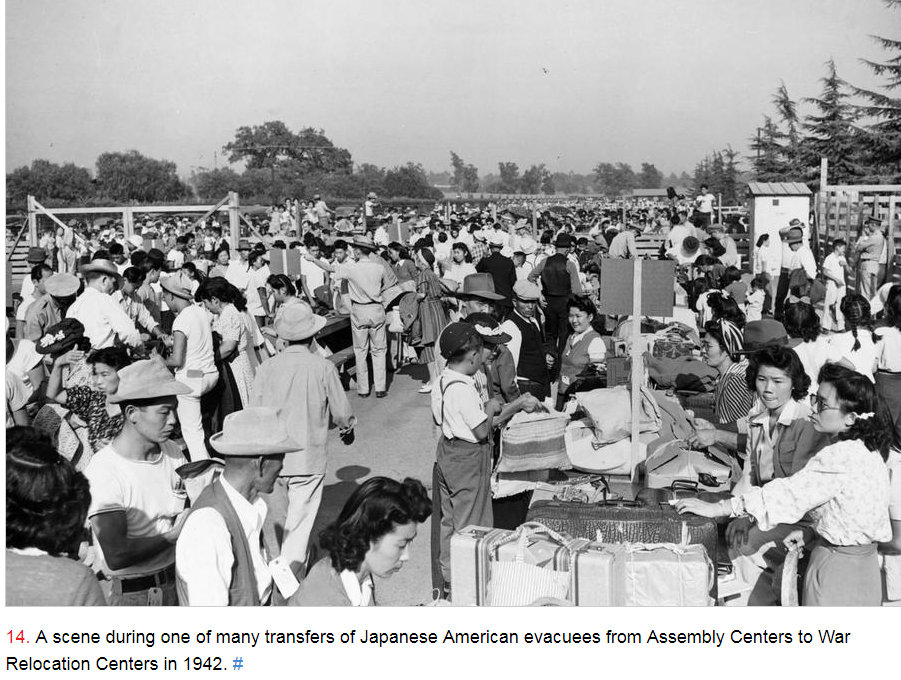

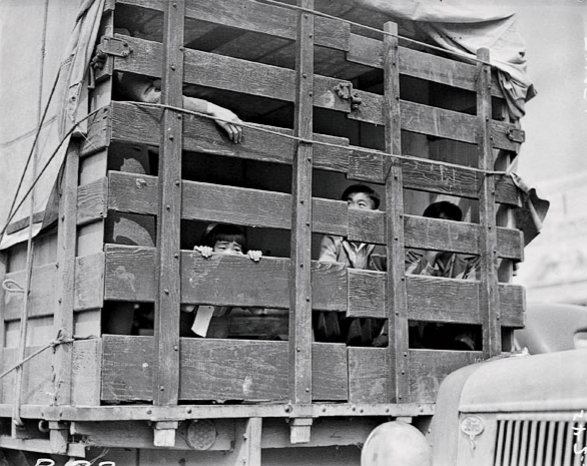

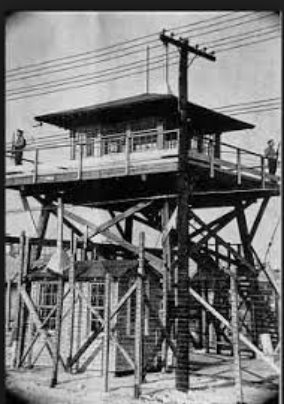

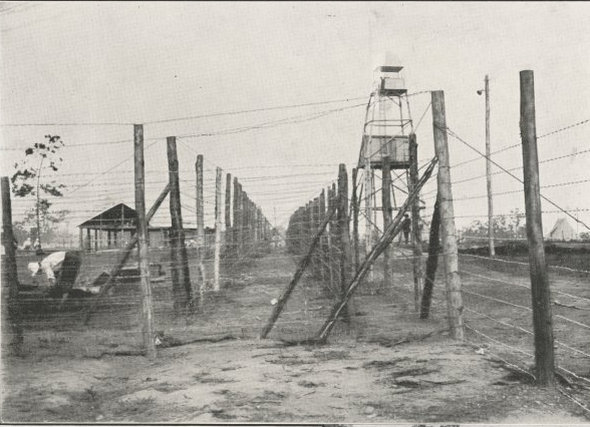

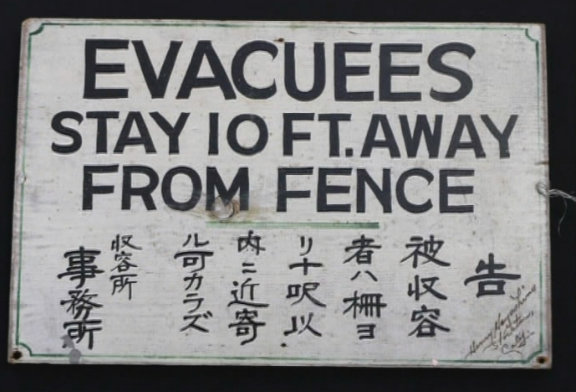

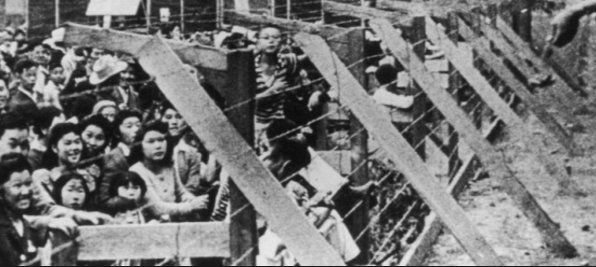

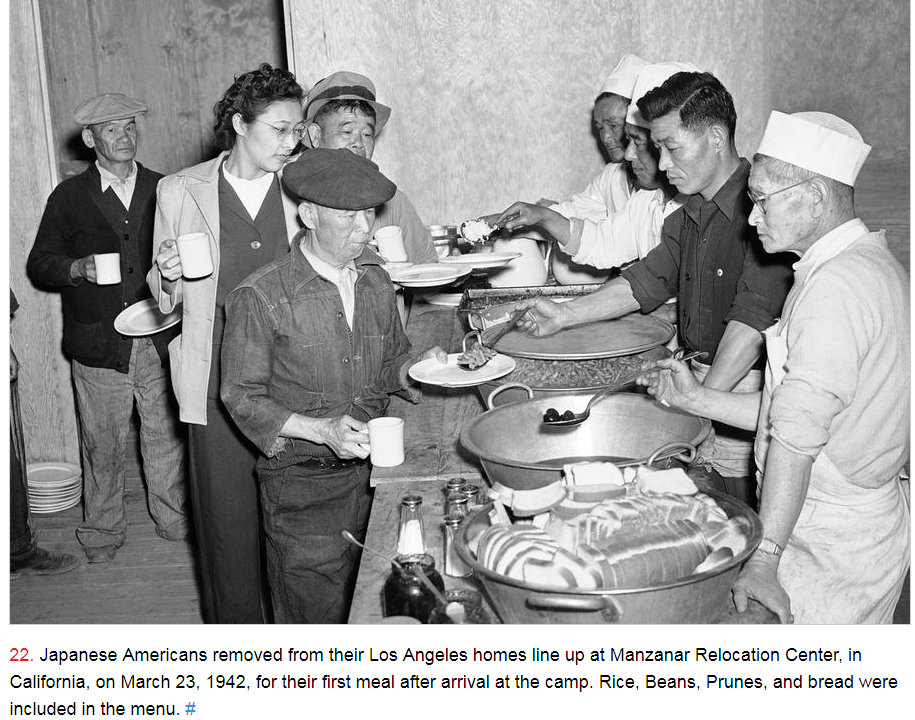

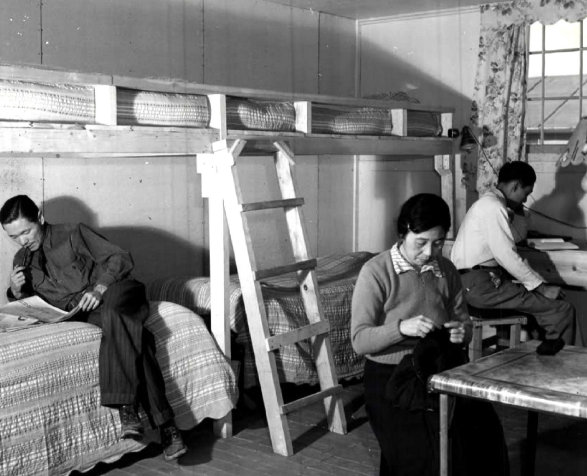

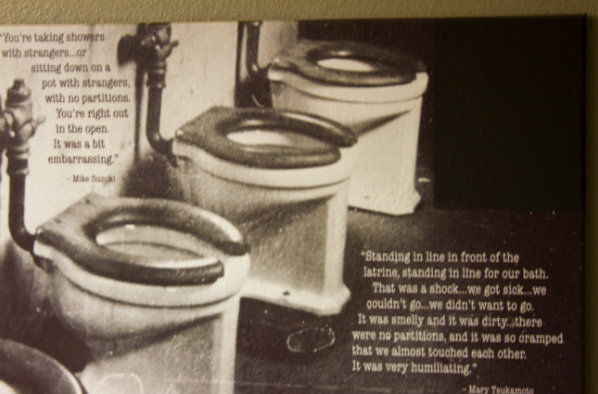

Allowed to only take bed linen, a few changes of clothing, a personal set of eating utensils and some toiletry articles, the internees were political prisoners left with little dignity as they were herded into the confines of barbed wire fenced enclosures as armed border agents in elevated towers stood guard. Family dynamics rapidly began to erode as multiple generations were forced into sharing living quarters with strangers in unfinished cold/hot and dusty tarpaper shanties with only straw-filled mattresses, a small stove to heat the room, and a single light bulb hanging from the ceiling. Lacking the basic amenities of running water, cooking and bathrooms facilities internees were subjected to communal un-partitioned showers, open toilets, and in Manzanar the constant threat of black widows spiders creeping out from dark crevices and agitated rattlesnakes coiled in corners ready to strike.

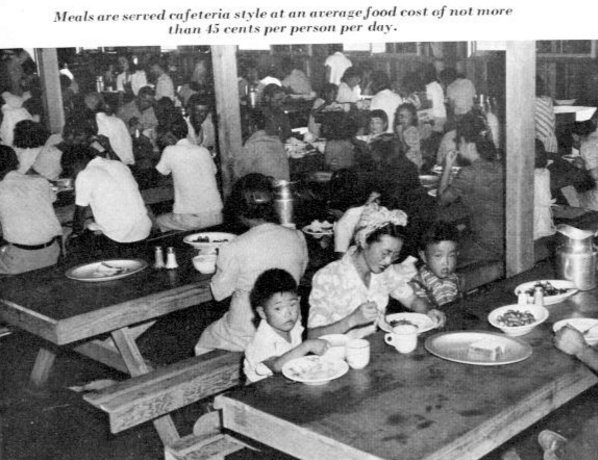

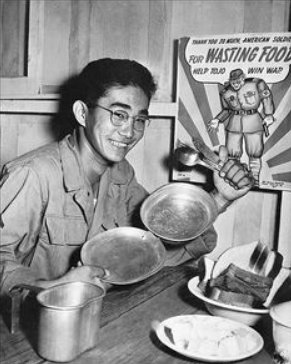

The social location of Japanese families gradually evolved into a new structural system of independence and disconnect from established traditions; Husbands felt shamed by their inability to protect and care for their families; with their patriarchy usurped many fell into the abyss of self-medicating with alcohol to relieve stress and feelings of inadequacy. Community dining hall bells announced meal time which served mystery meat and GI rations and rather than the accustomed family meals it became common for teens and children to eat with friends; Social construct flipped whereas before the Issei were in control, however, due to a better command of English the Nisei had the ability to secure better jobs and higher wages becoming the dominant force of family politics.

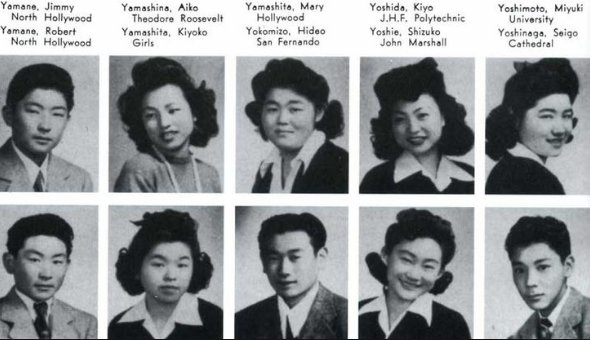

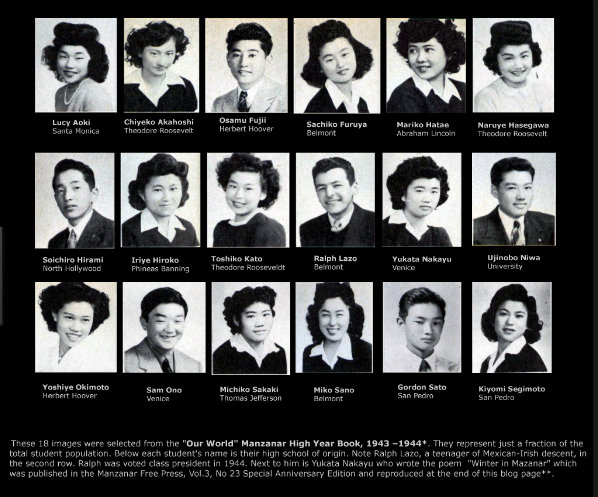

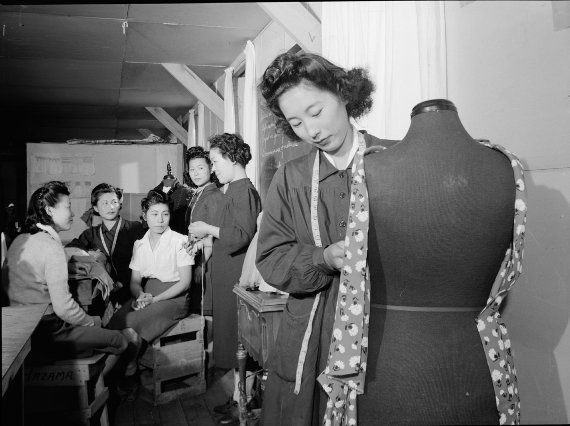

Women no longer sweated their lives away performing domestic duties giving them more time to socialize, learn hobbies and complete their educations. Students were able to excel without having to compete with White students for coveted scholarly positions and were eligible to participate in a number of programs unavailable to them in secular institutions. Young ladies of marrying age found love and weren’t bound by arranged marriages.

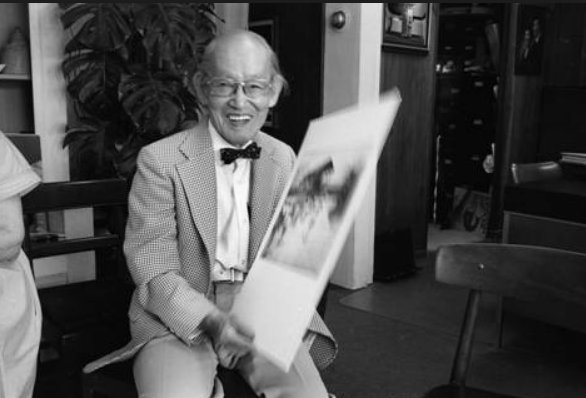

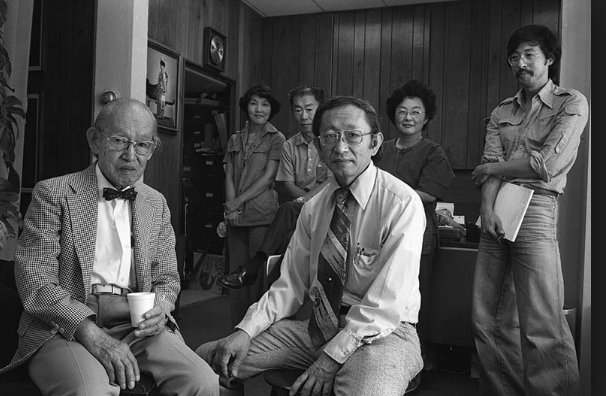

Rafu Shimpo appears to represent a whole generation of people from the elderly to the youngest, from full Japanese to mixed racial heritage; whereas prior to internment traditional Issei parents determined Nisei were only allowed to marry within their own ethnic culture.

Pre-internment workers and business owners were primarily physical laborers yet are now highly educated with degrees from prestigious universities and hold prominent positions in major companies, own multi-million dollar corporations, and reside in exclusive residential neighborhoods once reserved for “Whites Only.”

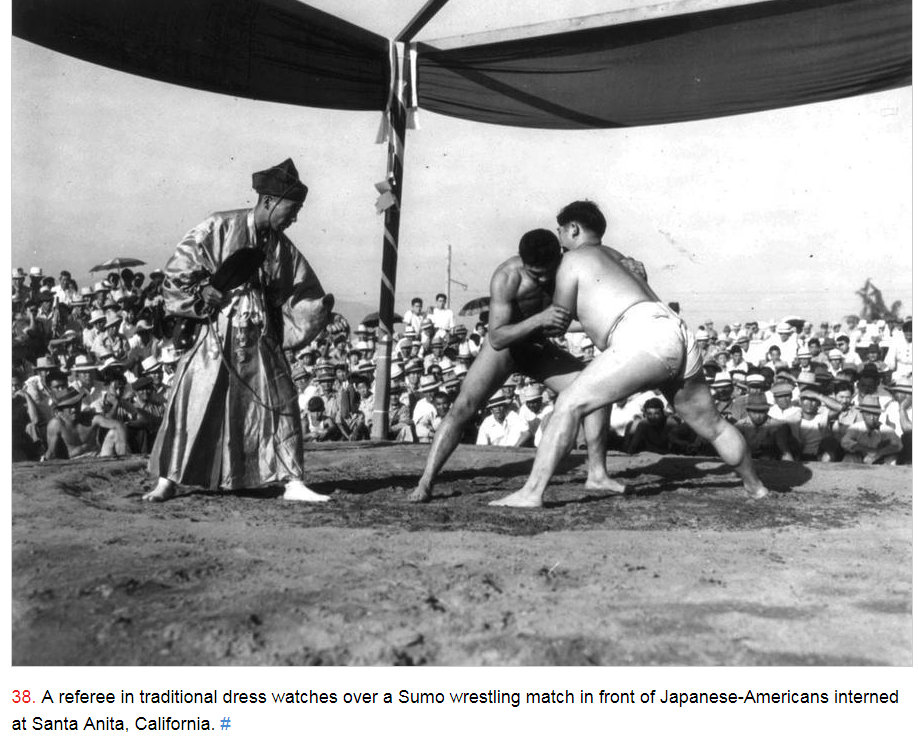

Traditional culture is still practiced within many of the communities to uphold long-established and time-honored celebrations and observances.

Examining the historical link between the past and present, the Japanese experience provides an inside look into the essence of how systems within communities continue to function successfully by integrating cultural traditions into the parameters of a governed dominant society.

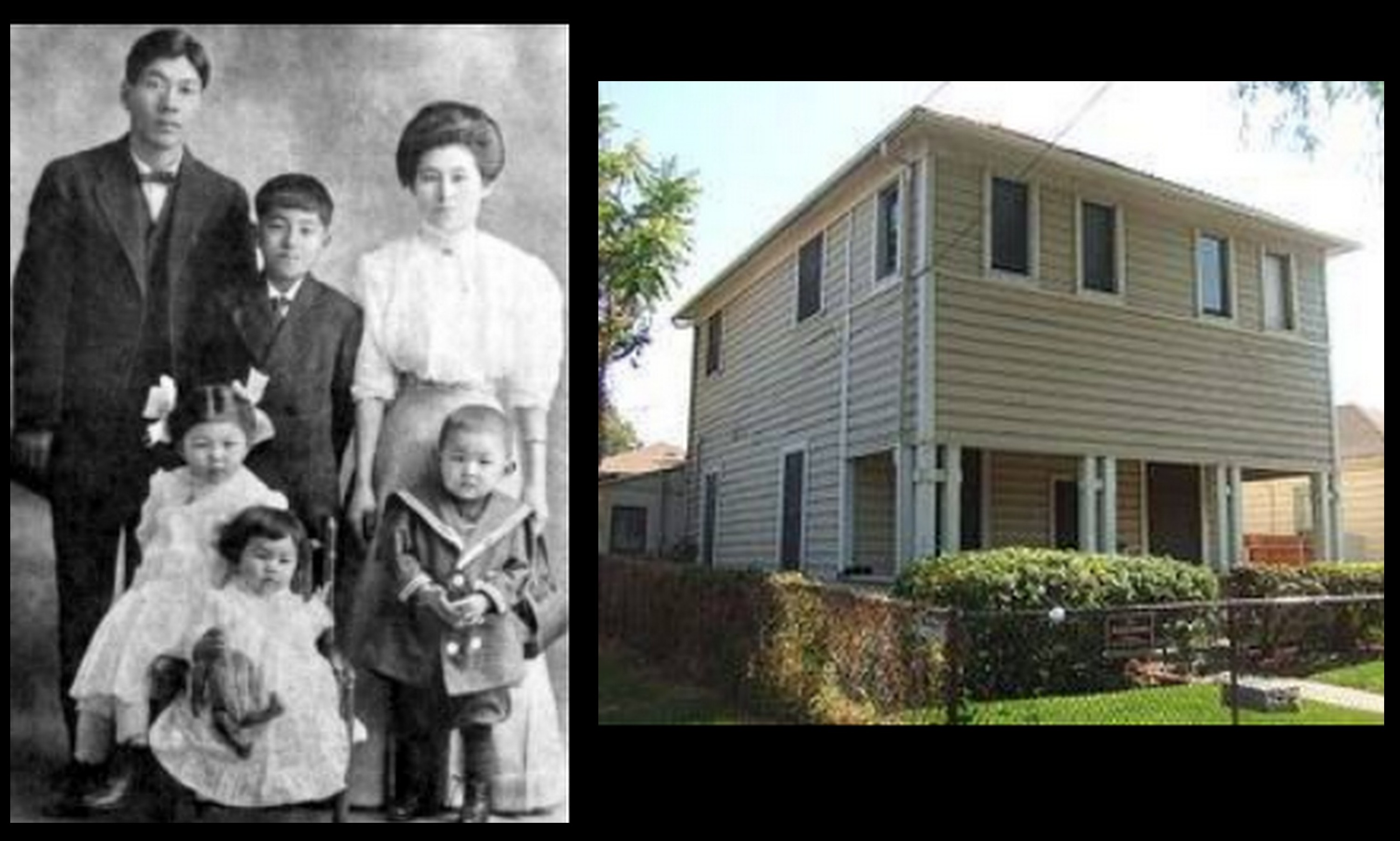

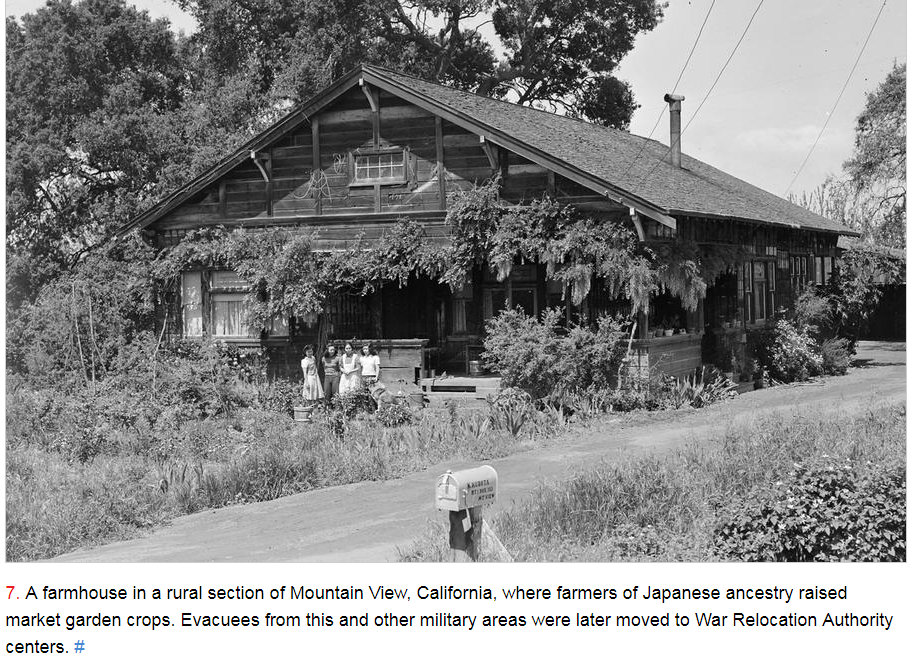

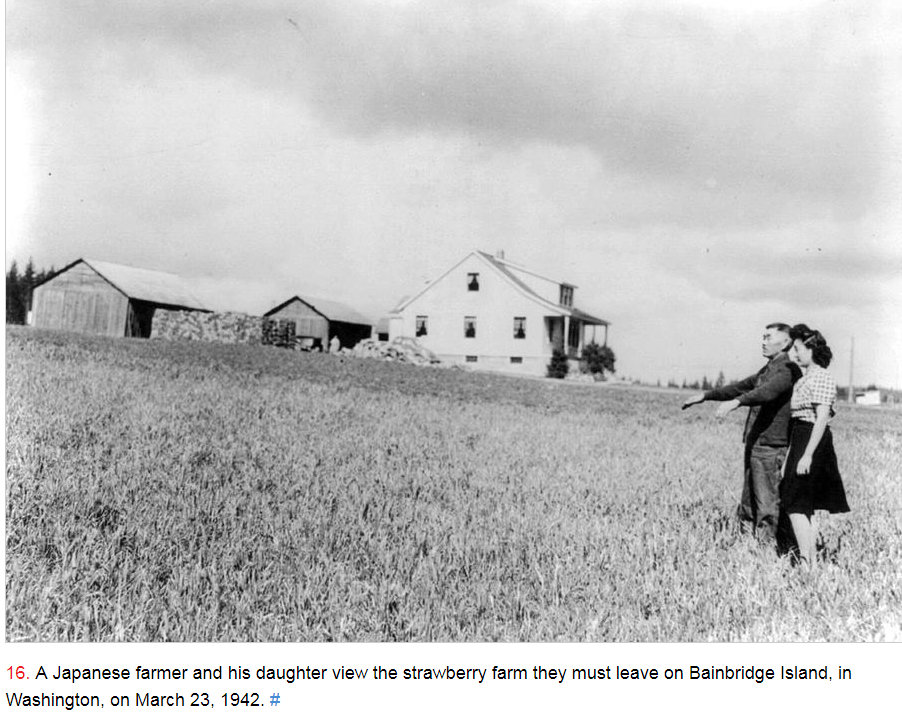

Prior to becoming *The New Enemy* and carted off to internment camps the majority of Japanese American families experienced a moderate level of racism typical for minority groups of that era. Pro-discrimination laws were passed in the early 1900s denied them the right to become citizens, own land, or marry outside their race. The 1907-1908 *Gentleman’s Agreement* consisting of informal letters between American and Japanese leaders virtually halted all Japanese contract labor to America and forbid the Japanese from buying homes in certain areas and barring them from jobs in various industries. By 1913 The California Alien Land Law prohibited Japanese as “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning agricultural land or possessing long-term farming leases. But for the most part the Japanese lived a peaceful life akin to other American families; owning or working in small businesses, children attending segregated public schools, men who voluntary joined the military and wives carrying out domestic duties.

In 1915, the courthouse in Riverside CA. recorded the deed of the house at 3356 Lemon Street in the names of Mine, Sumi, and Yoshizo Harada, the three minor American-born children of Jukichi and Ken Harada, Japanese immigrants living in Riverside. The deed was in the name of the children because the Alien Land Law of 1913 prevented the parents, aliens ineligible from citizenship, from owning property. Jukichi Harada was charged with violating the law. The People of the State of California v. Jukichi Harada became a test case and the state Supreme Court ruled the children could own the house. The Harada House was declared a National Landmark in 1990.

By 1924 immigration was completely blocked. In the early 1930s the visiting Captain of a cargo freighter docked in Santa Barbara was given a tour of the city while admiring the hillside scenery he lost his balance falling backward into a bed of cactus. People burst out laughing; not understanding American sense of humor, the Captain felt he was being ridiculed and lost face, he vowed to get revenge on Americans and on Santa Barbara. On Feb. 23, 1942, approximately 6 weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor the freighter Captain, who subsequently joined the Japanese navy as a submarine commander surfaced his submarine near an oil field pier just north of Santa Barbara and shelled the pier. Furthering the fear of *Japs*.

The Dec. 7th bombing of Pearl Harbor was quickly followed on Dec. 8, 1941, when FDR froze US citizen Isai assets and ordered the FBI to follow community leaders by imposing curfews and raiding homes for anything advocating a connection to Japan.

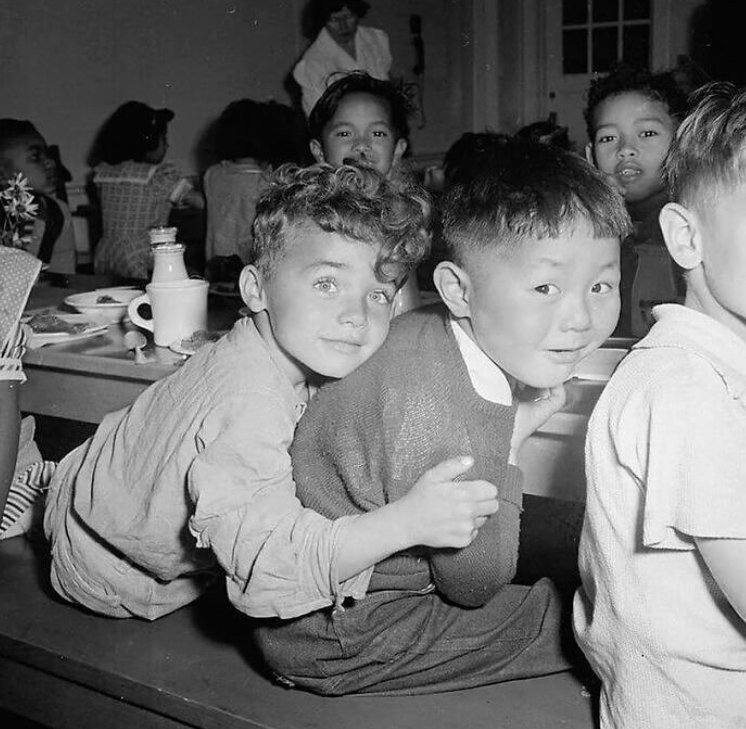

This photo; entitled ‘Lunch Hour’, was taken by Dorothea Lange at the Raphael Weill School in San Francisco – she captured the children together moments before the Japanese American population of the school was evacuated from the neighborhood.

Dorothea Lange’s censored photographs of the Japanese-American Internment

Yellow Peril Racism

They had about one week to dispose of what they owned, except what could be packed and carried for their departure by bus and were allowed only to take bed linen, a few changes of clothing, a personal set of eating utensils and some toiletry articles, the internees were political prisoners left with little dignity as they were herded into the confines of barbed wire fenced enclosures as armed border agents in elevated towers stood guard.

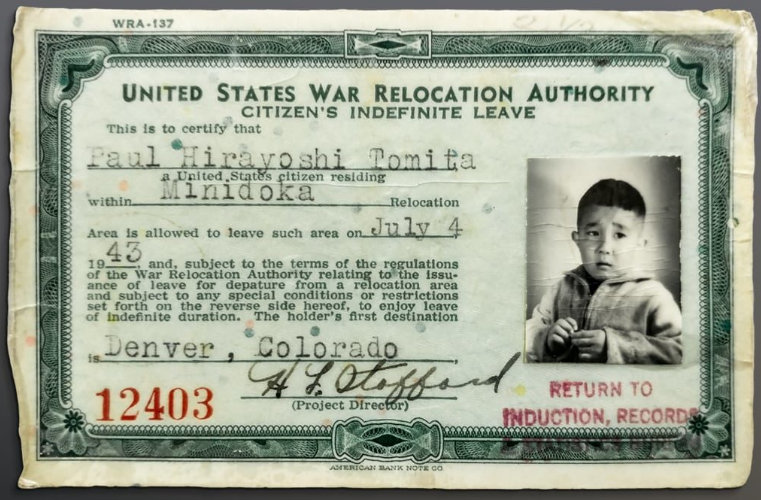

A Child’s Exit Card

It was Sunday, July 4, 1943. Four-year-old Paul Tomita was experiencing Independence Day, not with sparklers and parades, but by getting his right index finger inked. On that day, he was fingerprinted and photographed for a mint-green exit card that certified he was not a risk to national security. In the photo, Paul looks anxious and forlorn. “My parents are nervous and stressed out,” Paul, 79, says now, as he views the card. “And I know something is wrong.”

Continue Reading https://50objects.org/object/a-childs-identity-card/

May 9, 1942 Centerville CA Farm Families waiting to board the train

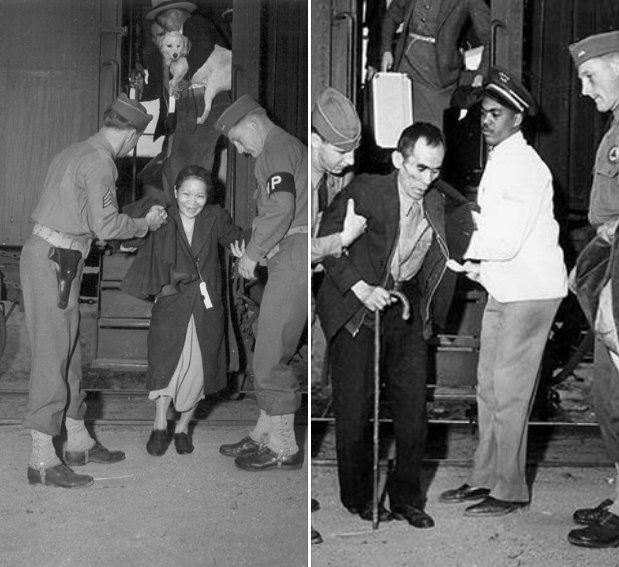

When the army rounded up and forcibly removed Japanese Americans from their homes in the spring of 1942, people were forbidden from bringing anything more than what they could carry – including any beloved dogs. However, we have heard a handful of stories of people who were able to sneak their dogs into Manzanar, and one story about family who was allowed to bring their dog with them.

Yoshisaburo Kitada was 63 years old when he and his family were forced to board a train to Manzanar. He was gravely ill with Parkinson ’s disease, and his dog provided comfort and assistance. In these two photos by WRA photographer Clem Albers, you can see the pup (maybe named “Miki”) being carried by a family member while they unloaded from a train at Lone Pine Depot, nine miles south of Manzanar. Sadly, Yoshisaburo passed away August 11, 1942, just four months after these photos were taken. He was survived by his wife, three children, and his loyal pup. Yoshisaburo’s granddaughter tells us that the dog lived through the incarceration, and after the war returned to Southern California with the Kitada family. Years later when it became ill, the dog waited until Yoshisaburo’s son returned home from work before it passed away.

Courtesy of Manzanar National Historic Site

https://tinyurl.com/y9ydteqf

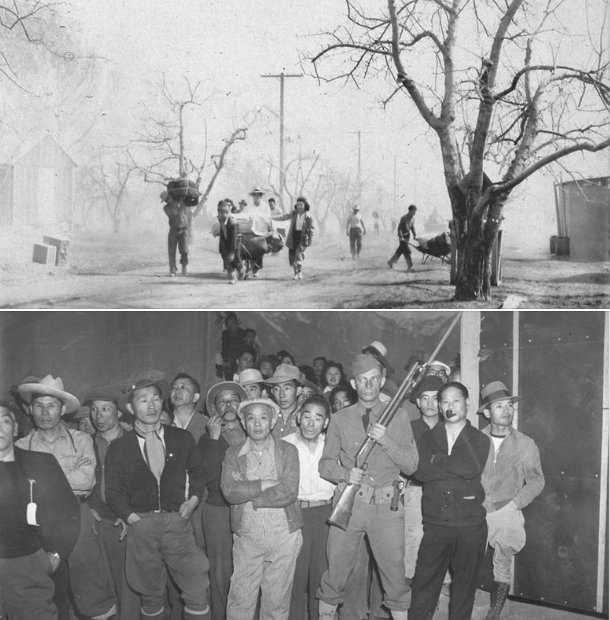

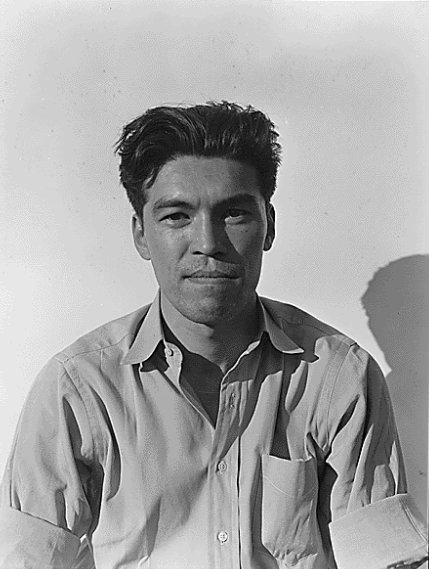

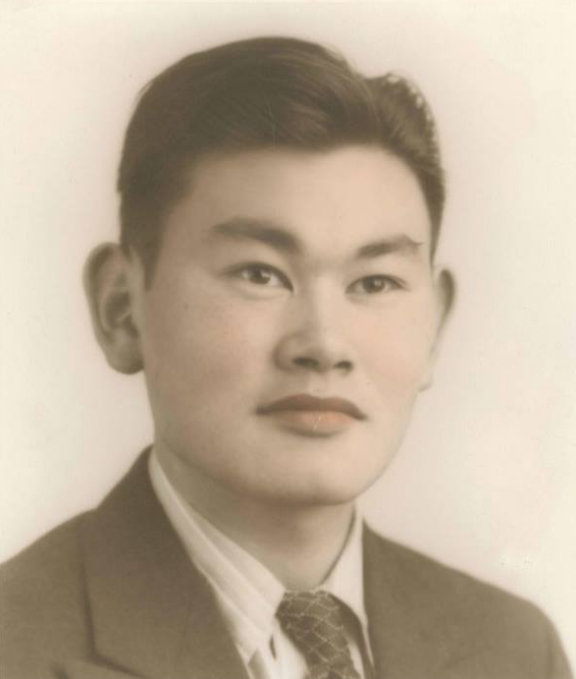

College student Shig Ochi was one of just over a thousand people who “volunteered” to come to Manzanar at the end of March 1942. A week and a half later, the first group of Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their homes under Executive Order 9066 would arrive on April Fools Day. “Volunteers” like Shig came early for a number of different reasons. Some intended to prepare the camp for family and friends. Others simply wished to face the inevitable without days or weeks of waiting. Yet many were surprised by what they found. In a 2007 oral history interview with Manzanar National Historic Site, Shig recalled:

“When Manzanar was being set up, there was a call for volunteers. I really did not have much enthusiasm for studying when the outlook was so gloomy, and at the urging of friends, they said I should volunteer for Manzanar because I would be helping my family out by doing so. So I volunteered. It was quite an experience to see the MPs when we got on this little train to go to Manzanar from downtown Los Angeles – Union Station I think… When we got to the camp…it was towards dusk. I guess they bused us from the train station and took us into the camp, and all of a sudden you find the next morning that you’re essentially incarcerated. I volunteered to go. You say, ‘Wait a minute.’ You’re volunteering and suddenly you’re behind bars.”

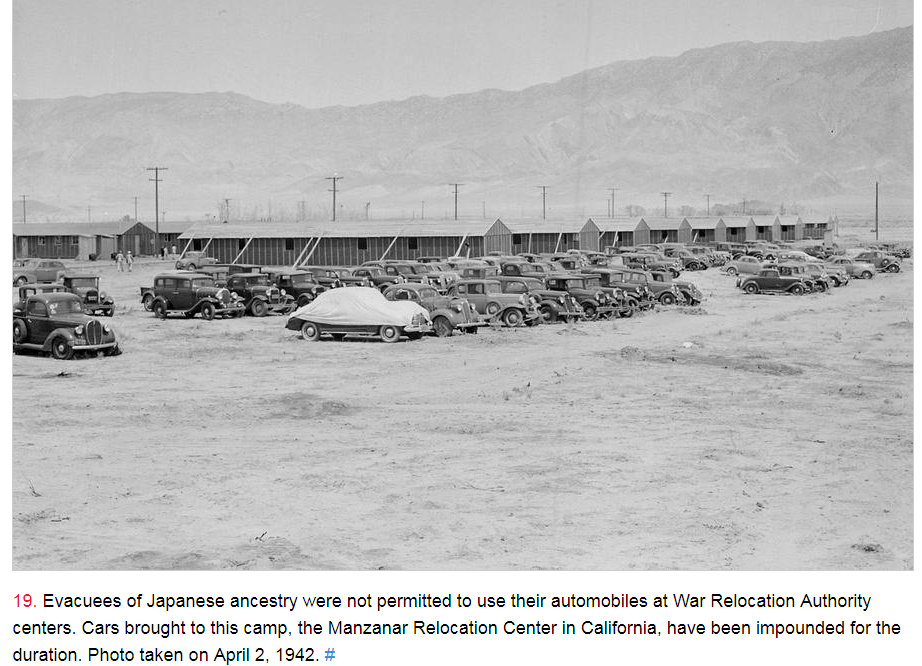

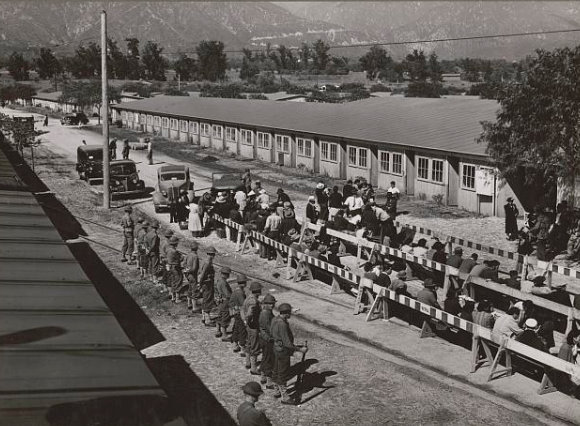

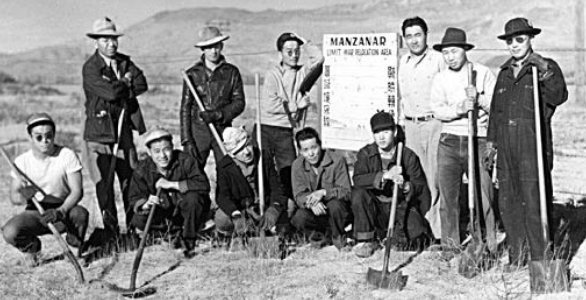

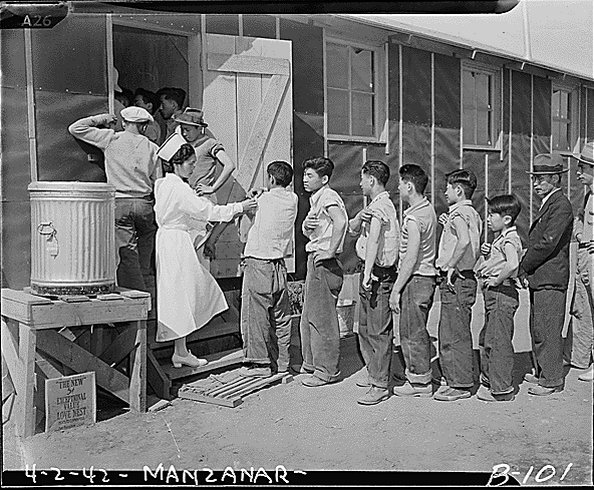

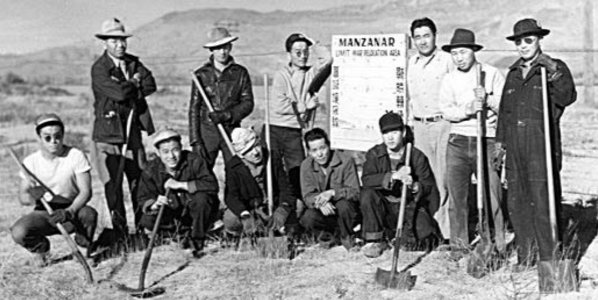

Clem Albers, a photographer hired by the War Relocation Authority, captured these two photographs on April 2, 1942. Though taken ten days after Shig Ochi arrived, they serve to illustrate the dusty, confined conditions Japanese Americans faced when they first set foot in Manzanar. Some would remain incarcerated here for the next three and a half years.

Courtesy of Manzanar National Historic Site

https://tinyurl.com/y9ydteqf

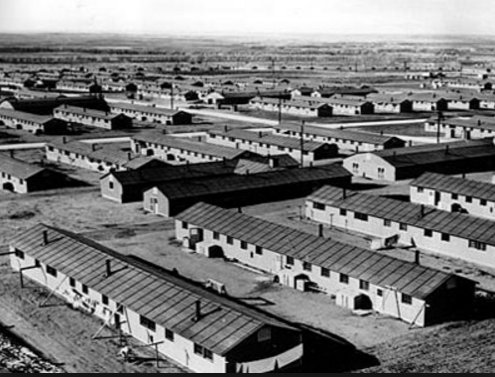

First evacuees arrival at Granada Internment Camp

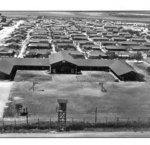

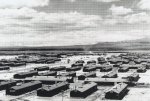

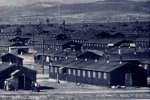

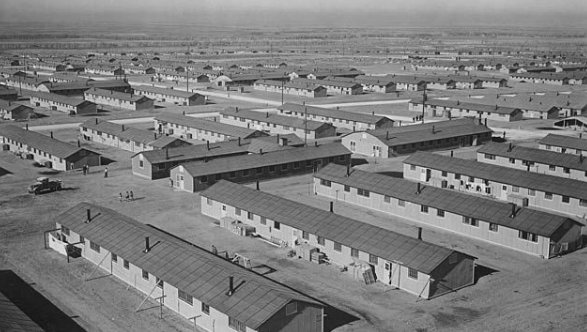

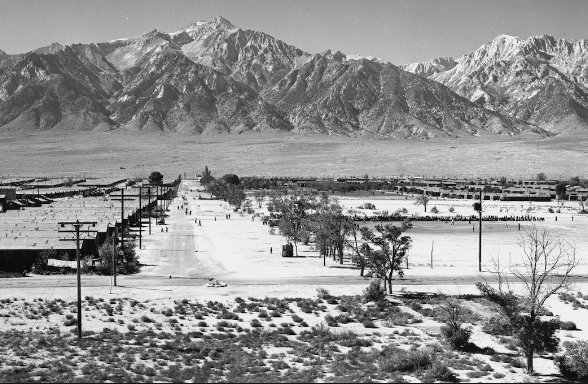

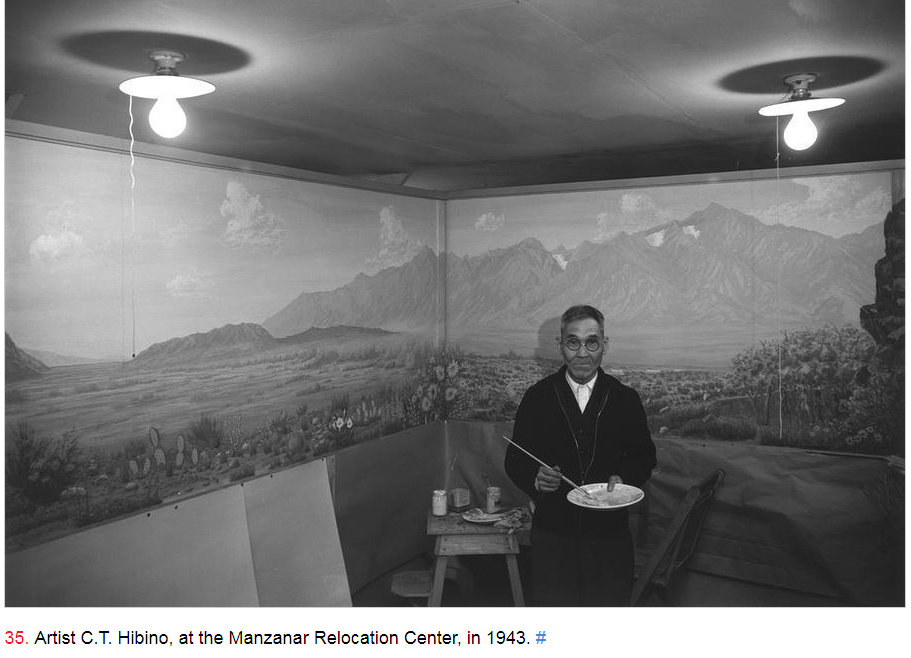

The most notorious camp was Manzanar, built at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountain range 230 miles northeast of Los Angeles. At its peak, over 10,000 people were interned in the 500-acre camp, enclosed by barbed wire, guard towers and armed military police.

Conditions at the camp were unforgiving. Daytime temperatures could reach 110 degrees, while nights could be freezing. Dust and wind were constant, and the crude barracks provided poor shelter. Within these barracks, each family was allotted a 20-by-25-foot cloth partition.

Most of the internees resolved to make the best of their situation, by attempting to create some semblance of normalcy for their indefinite detention. Some built all the facilities and trappings necessary to maintain a community of 10,000.

Japanese waiting for registration at the Santa Anita Reception Center (Photo by Russell Lee)

Some letters arriving from Japanese-American Internment Camps during WWll were very specific asking for a certain kind of bath powder, cold cream or cough drops.

Family dynamics rapidly began to erode as multiple generations were forced into sharing living quarters with strangers in unfinished cold/hot and dusty tarpaper shanties with only straw-filled mattresses, a small stove to heat the room, and a single light bulb hanging from the ceiling.

Amache Japanese Internment Camp

Looking back on Ansel Adams photographs of Japanese Interment Camp

Orphaned infants incarcerated at the Manzanar Children’s Village, some with as little as 1/8th Japanese ancestry were ripped from orphanages.

Lacking the basic amenities of running water, cooking and bathrooms facilities internees were subjected to communal un-partitioned showers, open toilets, and in Manzanar the constant threat of black widows spiders creeping out from dark crevices and agitated rattlesnakes coiled in corners ready to strike.

The social location of Japanese families gradually evolved into a new structural system of independence and disconnect from established traditions; Husbands felt shamed by their inability to protect and care for their families; with their patriarchy usurped many fell into the abyss of self-medicating with alcohol to relieve stress and feelings of inadequacy.

Community dining hall bells announced meal time which served mystery meat and GI rations, and rather than the accustomed family meals it became common for teens and children to eat with friends.

Manzanar teen getting ready to have breakfast

A life Beyond Limits

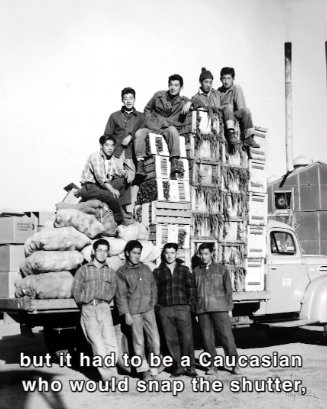

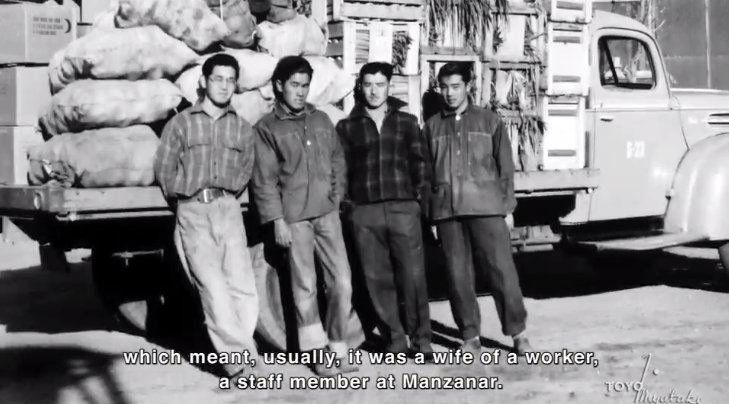

Potato Field shows people working against the vast backdrop of the High Sierra’s

Social construct flipped whereas before the Issei were in control, however due to a better command of English the Nisei had the ability to secure better jobs and higher wages thus becoming the dominant force of family politics.

The first grave at Manzanar Center Cemetery

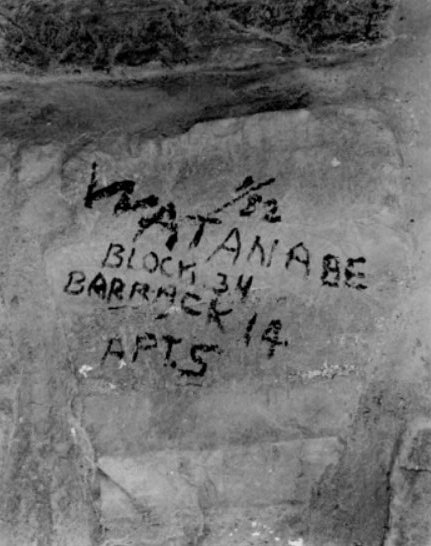

Mr. Watanabe’s signature carved into a low bordering wall

High schooler’s attend a science lecture

High schooler’s attend a science lecture

Women no longer sweated their lives away performing domestic duties giving them more time to socialize, learn hobbies and complete their educations. Students were able to excel without having to compete with White students for coveted scholarly positions and were eligible to participate in a number of programs unavailable to them in secular institutions. Young ladies of marrying age found love and weren’t bound by arranged marriages.

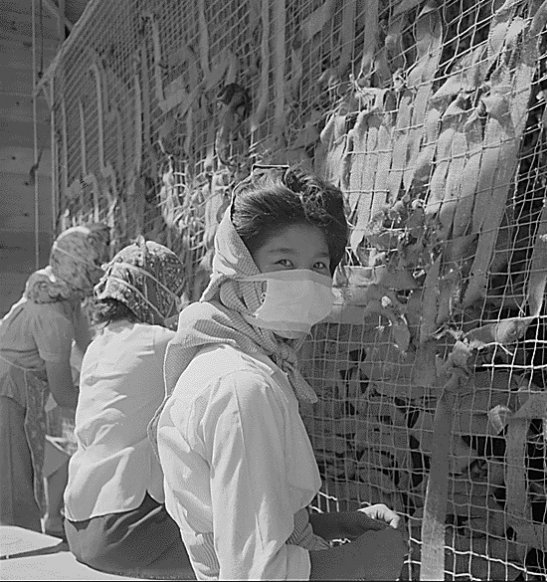

Dorthea Lange

Japanese American internees making camouflage netting at Manzanar. Photo Dorthea Lange July 1, 1944

Mrs. Dennis Shimizu

Kiyo Yoshida, Lillian Wakatsuki and Yoshiko Yamasaki attend a high school biology class.

Kiyo Yoshida, Lillian Wakatsuki and Yoshiko Yamasaki attend a high school biology class.

The Manzanar Fishing Club.

Minidota MN Family

May 11, 1942 A 23 yr old soldier and his mother in a strawberry field near Florin CA – The soldier had volunteered for the Army on July 10, 1941, and was stationed at Camp Leonard Wood, Missouri. He was furloughed to help his mother and family prepare for their evacuation. He is the youngest of six children, two of them volunteers in United States Army. The mother, age 53, came from Japan 37 years before. Her husband had passed away 21 years prior leaving her to raise six children. She worked in a strawberry basket factory until 1945(?) when her children leased three acres of strawberries “so she wouldn’t have to work for somebody else.

May 11, 1942 A 23 yr old soldier and his mother in a strawberry field near Florin CA – The soldier had volunteered for the Army on July 10, 1941, and was stationed at Camp Leonard Wood, Missouri. He was furloughed to help his mother and family prepare for their evacuation. He is the youngest of six children, two of them volunteers in United States Army. The mother, age 53, came from Japan 37 years before. Her husband had passed away 21 years prior leaving her to raise six children. She worked in a strawberry basket factory until 1945(?) when her children leased three acres of strawberries “so she wouldn’t have to work for somebody else.

A Japanese Pleasure Garden built by Internees

A Japanese Pleasure Garden built by Internees

Dec. 31, 1942 photo by Frances Stewart

Nakamura with her two daughters “Joyce Yuki” and “Louise Tami” walking under a Japanese Style Pavillion. Manzanar Relocation Camp, Owens Valley California

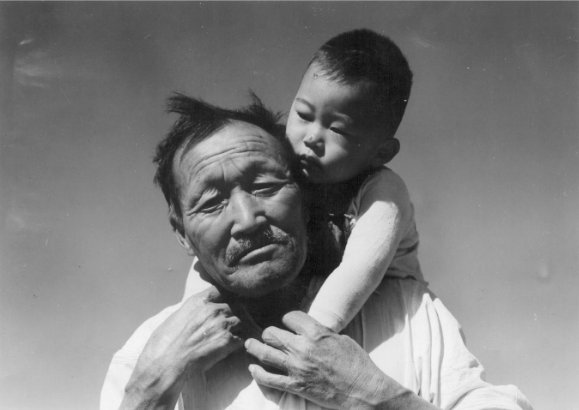

Manzanar, Calif.–Grandfather and grandson of Japanese ancestry at this War Relocation

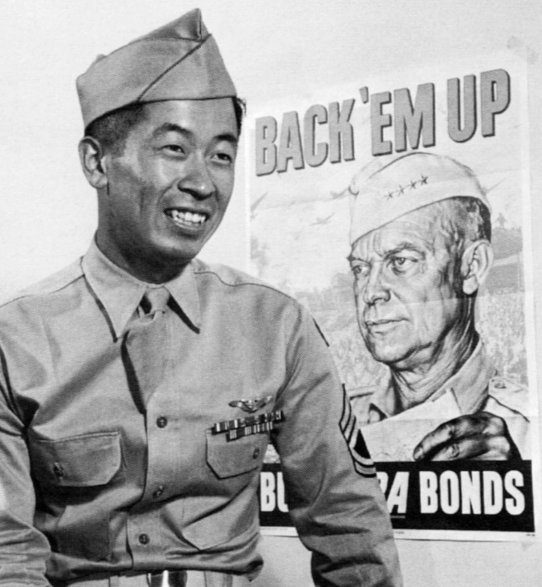

Joe Blamey Editor Manzanar Free Press  Ben Kuroki, the son of Japanese immigrants who was raised on a Hershey NB farm, is seen in this updated Army Corps file photo. The only known Japanese-American known to have flown over Japan during WWll

Ben Kuroki, the son of Japanese immigrants who was raised on a Hershey NB farm, is seen in this updated Army Corps file photo. The only known Japanese-American known to have flown over Japan during WWll

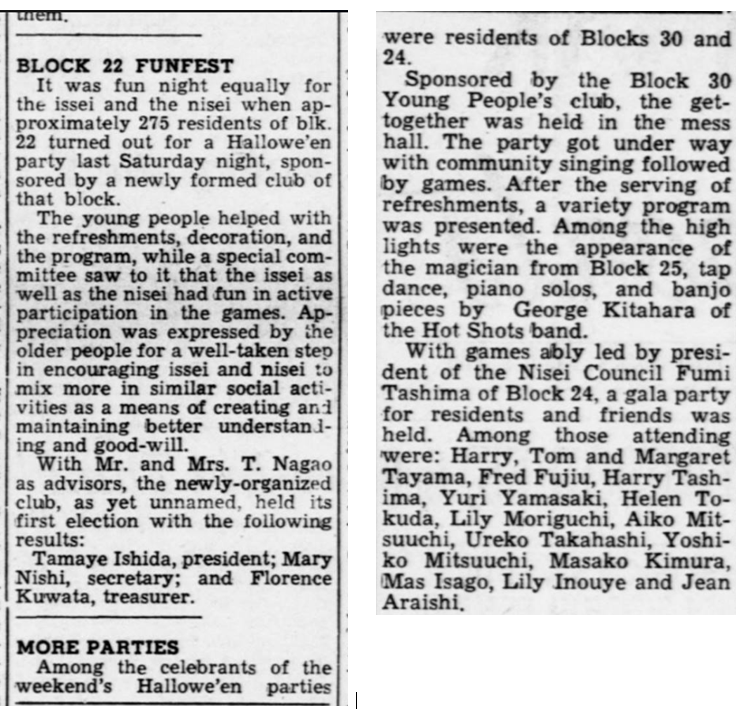

Japanese Americans incarcerated in Manzanar from 1942 to 1945 celebrated Halloween behind barbed wire. Articles from the Manzanar Free Press provide insight into what kinds of Halloween parties people held mostly in block mess halls, as a rather intimidating warning to children, that Japanese American policemen in Manzanar wore uniforms of green pants and red shirts. A photo of a children’s Halloween party in the Block 20 mess hall, taken by Toyo Miyatake in 1943 or 1944, shows a “carved pumpkin” created from paper in the absence of real pumpkins, and on the plate of each child a large pear, possibly harvested from Manzanar’s many pear orchards which had been planted decades before WWII.

The Rafu Shimpo Newspaper appears to represent a whole generation of people from the elderly to the youngest, from full Japanese to mixed racial heritage; whereas prior to internment traditional Issei parents determined Nisei were only allowed to marry within their own ethnic culture.

Mary “Mollie” Oyama Mittwer as *Deirde* (1907–1994) was a Nisei journalist whose writing reflected many of the issues her generation faced during World War II. A leading writer of her generation, *Deirde* dispensed wisdom and controversy through various advice columns and articles, giving Nisei women and men a chance to voice opinions and receive feedback regarding the do’s and don’t’s of delicate topics such as dating and marriage, racism and integration and fielding questions mainly centering on the private lives of people concerned with arranged marriage vs voluntarily marrying for love, interracial and interethnic dating, fashion advice, incorporating Japanese traditions into modern day society while continuing to maintain the cultural standards their parents and grandparents expected.

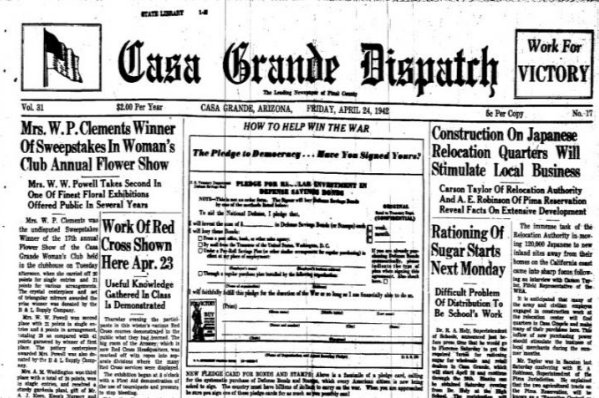

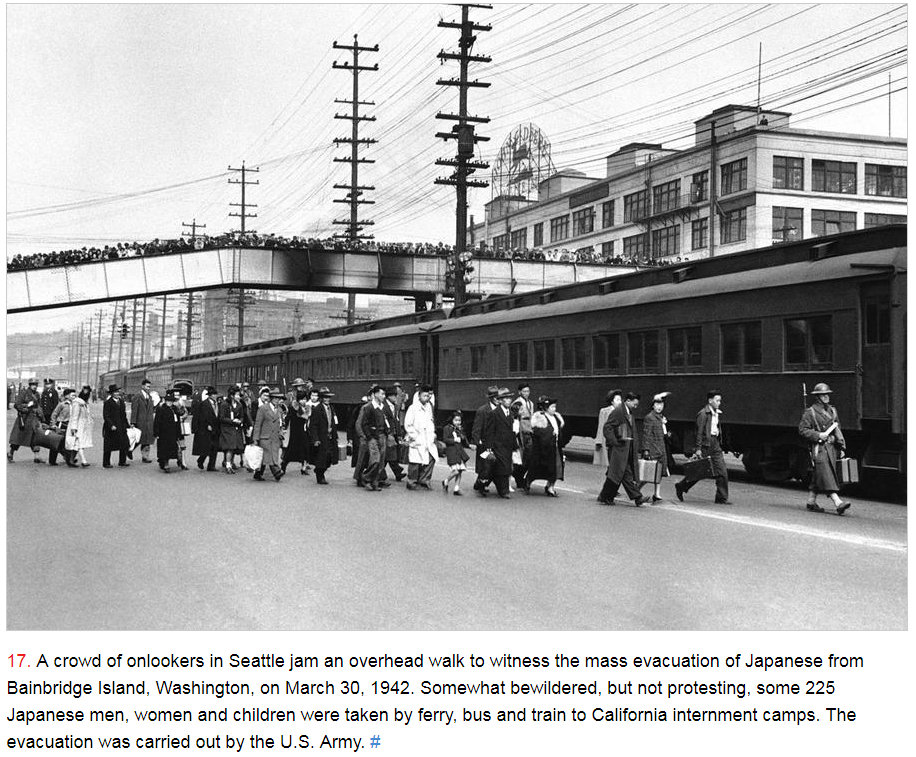

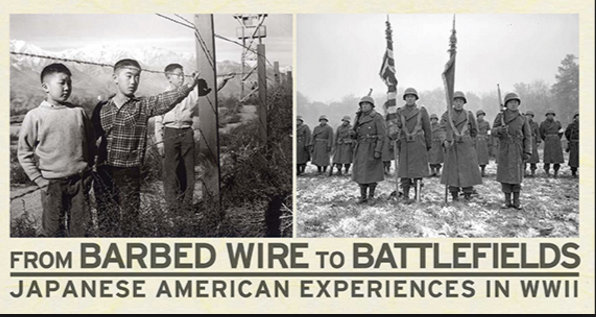

The internment of Japanese Americans in the United States during World War II was the forced relocation and incarceration in camps in the interior of the country of between 110,000 and 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry who had lived on the Pacific coast. Sixty-two percent of the internees were United States citizens.

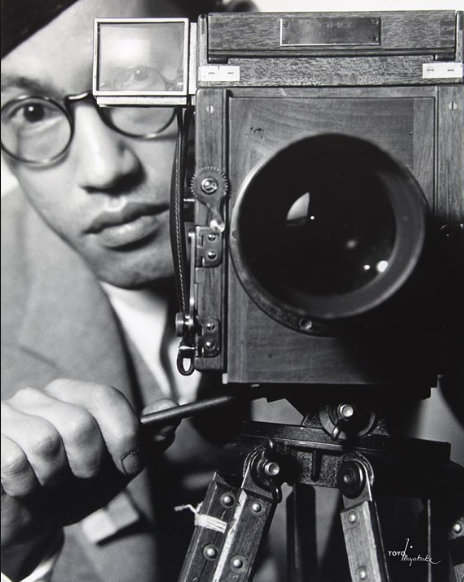

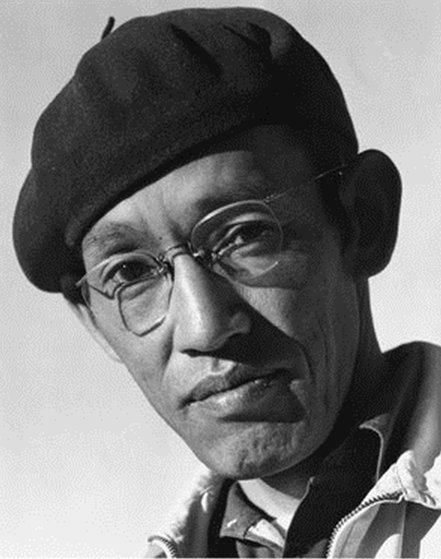

Ansel Adams took this picture of fellow photographer Toyo Miyatake, who was interned at Manzanar. Ansel Adams/Courtesy Photographic Traveling Exhibitions

The majority of photographs on this page were taken by Mr. Miyatake.

Before World War II, Miyatake had a photo studio in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo. When he learned he would be interned at Manzanar, he asked a carpenter to build him a wooden box with a hole carved out at one end to accommodate a lens. He turned this box into a makeshift camera that he snuck around the camp, as his grandson Alan Miyatake explains in the video below, which is featured in the exhibit.

Fearful of being discovered, Miyatake at first only took pictures at dusk or dawn, usually without people in them. Camp director Merritt eventually caught Miyatake, but instead of punishing him, allowed him to take pictures openly. Miyatake later became the camp’s official photographer, however, he could only set up the camera, and set up the shot, but a White person had to snap the shutter.

His photos convey an intimacy with camp life absent in the pictures that Adams and Lange took. He captured laughter at a picnic and men delivering vegetables to the mess hall.

His photos also had moments of silent protest. In one picture three boys peer through the camp’s barbed wire fence to the outside world. And in another, Miyatake’s son, Archie, holds a pair of clippers against the fence, “to show,” that at some point, the barbed wire has to come down.”

Toyo Miyatake as Grand Marshal

Toyo Miyatake 1977

1977 Two Views of Manzanar – Co-Curator Patrick Nagatani ~ Photography by Graham Howe

Fred Korematsu decided to test the government relocation action in the courts. He found little sympathy there. In KOREMATSU VS. THE UNITED STATES, the Supreme Court justified the executive order as a wartime necessity. When the order was repealed, many found they could not return to their hometowns. Hostility against Japanese Americans remained high across the West Coast into the postwar years as many villages displayed signs demanding that the evacuees never return. As a result, the interns scattered across the country.

In 1988, Congress attempted to apologize for the action by awarding each surviving intern $20,000. While the American concentration camps never reached the levels of Nazi death camps as far as atrocities are concerned, they remain a dark mark on the nation’s record of respecting civil liberties and cultural differences.

First, second, third, fourth and fifth generation of immigrants

Issei (一世 born in Japan immigrated to North America.

Nisei (二世 (second generation) children born in North America whose parents were immigrants from Japan.

Sansei (三世 (third generation) grandchildren of the Issei

Yonsei (四世 fourth generation

Gosei (五省 fifth generation

Obāsan お婆さん aunt or older woman generally referring to the grandmother of a Sansei

Ojiisan おじいさん general term for older men but generally referring to the grandfather of a Sansei

Nikkei (日系) was coined by a multinational group of sociologists and encompasses all of the world’s Japanese immigrants across generations. The collective memory of the Issei and older Nisei was an image of Meiji Japan from 1870 through 1911, which contrasted sharply with the Japan that newer immigrants had more recently left. These differing attitudes, social values and associations with Japan were often incompatible with each other. In this context, the significant differences in post-war experiences and opportunities did nothing to mitigate the gaps which separated generational perspectives.

1943 Manzanar Relocation Center taken by Ansel Adams – L to R – Mrs. Kay Kageyama, Toyo Miyatake (photographer), Miss Tetsuko Murakam, Mori Nakashima, Joyce Yuki Nakamura (eldest daughter), Corporal Jimmy Shohara, Aiko Hamaguchi (Nurse), Yoshio Muramoto, (electrician).

In 1942 Fred Korematsu refused to follow orders to be incarcerated along with 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry living on the West coast of the United States. In 1944, his case reached the Supreme Court. Justice Roberts, in dissent of the opinion of the court, wrote:

“The indisputable facts exhibit a clear violation of constitutional rights… It is a case of convicting a citizen as punishment for not submitting to imprisonment in a concentration camp, based on his ancestry, and solely because of his ancestry, without evidence or inquiry concerning his loyalty and good disposition toward the United States.”

In 1983, when U.S. District Court Judge Marilyn Hall Patel vacated Korematsu’s conviction, she said the case is a “caution that in times of distress the shield of military necessity and national security must not be used to protect governmental actions from close scrutiny and accountability.”

Fred Korematsu himself feared, “As long as my record stands in federal court, any American citizen can be held in prison or concentration camps without a trial or a hearing.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vpn3k8mxjqY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DxekM4zGAhY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=per594QmeE4

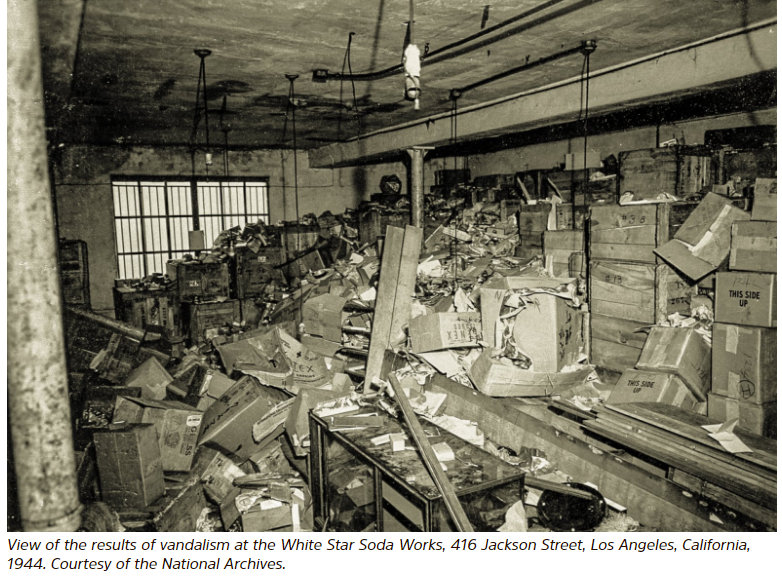

Many people who stored their belongings in commercial places came back to find that everything had been looted and they had no recourse but to start all over from nothing.

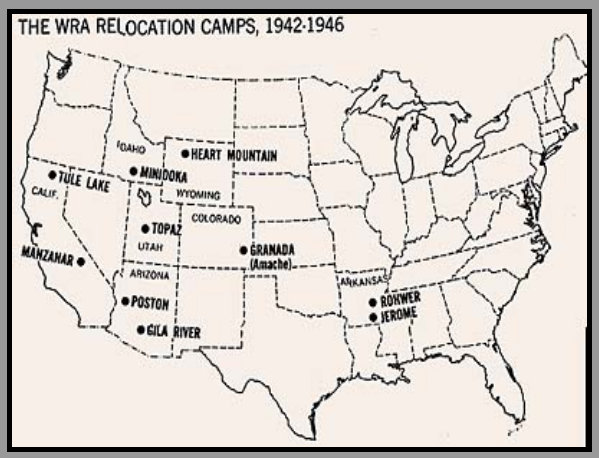

DETENTION CAMPS

Permanent detention camps that held internees from March, 1942 until their closing in 1945 and 1946.

Click on Photos for Enlarged Slideshow

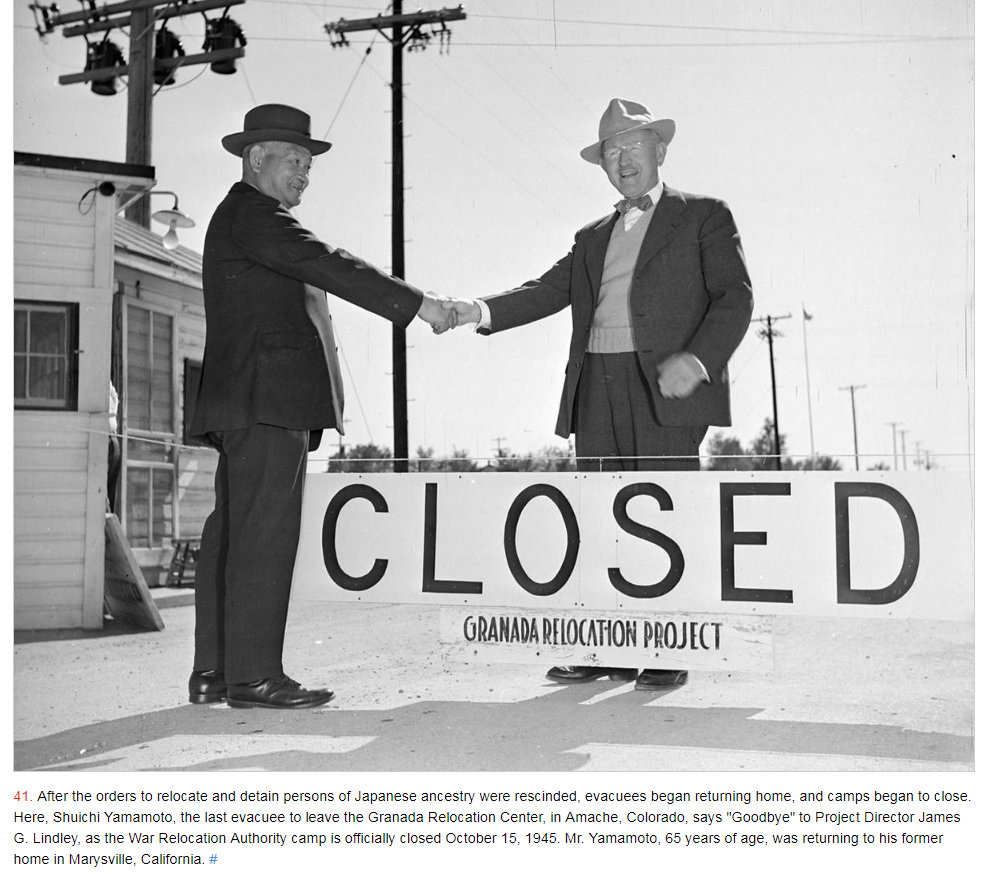

AMACHE

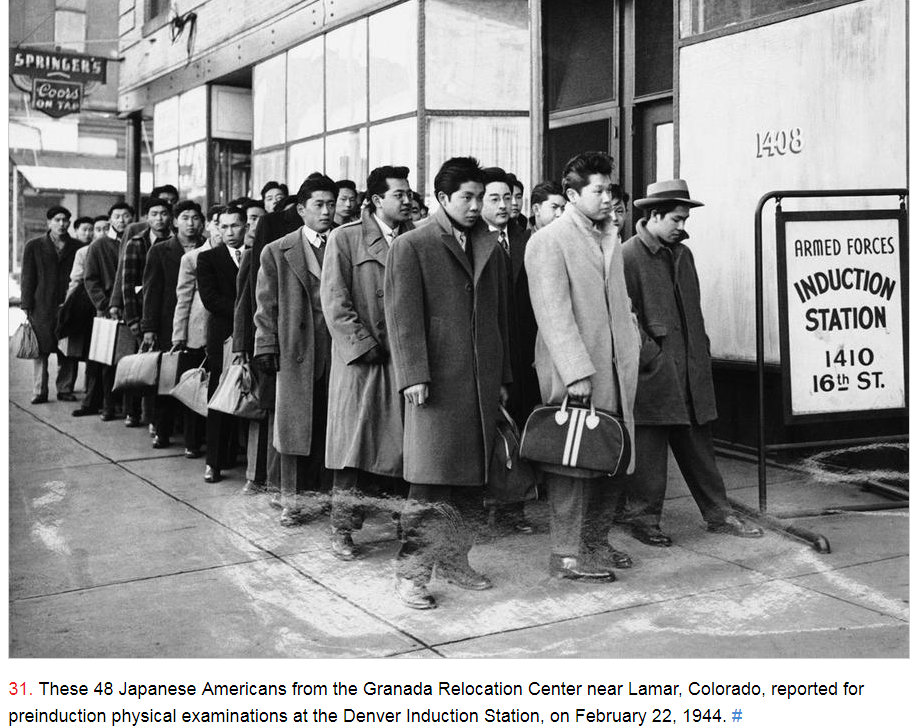

Granada, Colorado Opened August 24, 1942. Closed October 15, 1945. Peak population 7318. Origin of prisoners: Nothern California coast, West Sacramento Valley, Northern San Joaquin Valley, Los Angeles. 31 Japanese Americans from Amache volunteered and lost their lives in World War II. 120 died here between August 27, 1942 and October 14, 1945. In April, 1944, 36 draft resisters were sent to Tucson, AZ Federal Prison.

Drone used to create 3D reconstruction of Japanese internment camp in southern Colorado

https://tinyurl.com/yxbn9ux8

GILA RIVER

Arizona Opened July 20, 1942. Closed November 10, 1945. Peak Population 13,348. Origin of prisoners: Sacramento Delta, Fresno County, Los Angeles area. Divided into Canal Camp and Butte Camp. Over 1100 citizens from both camps served in the U.S. Armed Services. The names of 23 war dead are engraved on a plaque here. The State of Arizona accredited the schools in both camps. 97 students graduated from Canal High School in 1944. Nearly 1000 prisoners worked in the 8000 acres of farmland around Canal Camp, growing vegetables and raising livestock.2

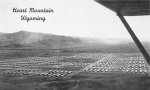

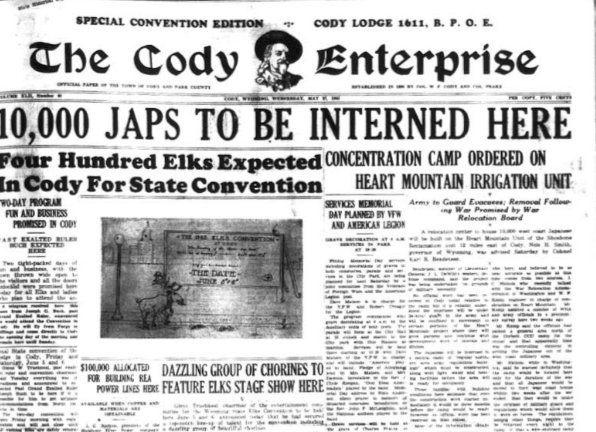

HEART MOUNTAIN

Wyoming Opened August 12, 1942. Closed November 10, 1945. Peak population 10,767. Origin of prisoners: Santa Clara County, Los Angeles, Central Washington. In November, 1942, Japanese American hospital workers walked out because of pay discrimination between Japanese American and Caucasian American workers. In July, 1944, 63 prisoners who had resisted the draft were convicted and sentenced to 3 years in prison. The camp was made up of 468 buildings, divided into 20 blocks. Each block had 2 laundry-toilet buildings. Each building had 6 rooms each. Rooms ranged in size from 16′ x 20′ to 20′ x 24′. There were 200 administrative employees, 124 soldiers, and 3 officers. Military police were stationed in 9 guard towers, equipped with high beam searchlights, and surrounded by barbed wire fencing around the camp.

JEROME

Arkansas Opened October 6, 1942. Closed June 30, 1944. Peak population 8497. Origin of prisoners: Central San Joaquin Valley, San Pedro Bay area. After the Japanese Americans in Jerome were moved to Rohwer and other camps or relocated to the east in June, 1944, Jerome was used to hold German POWs.

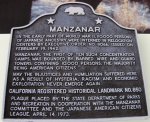

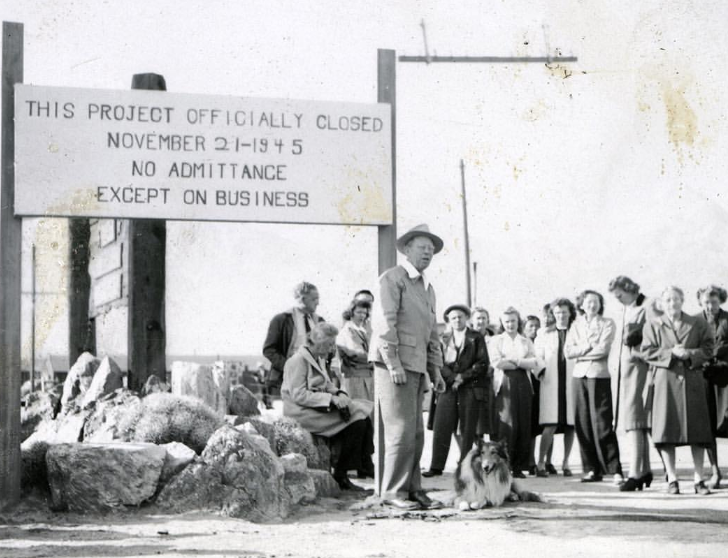

MANZANAR

California Opened March 21, 1942. Closed November 21, 1945. Peak population 10,046. Origin of prisoners: Los Angeles, San Fernando Valley, San Joaquin County, Bainbridge Island, Washington. It was the first of the ten camps to open — initially as a processing center.

MINIDOKA

Idaho Opened August 10, 1942. Closed October 28, 1945. Peak population 9397. Origin of prisoners: Seattle and Pierce County, Washington, Portland and Northwestern Oregon. 73 Minidoka prisoners died in military service.

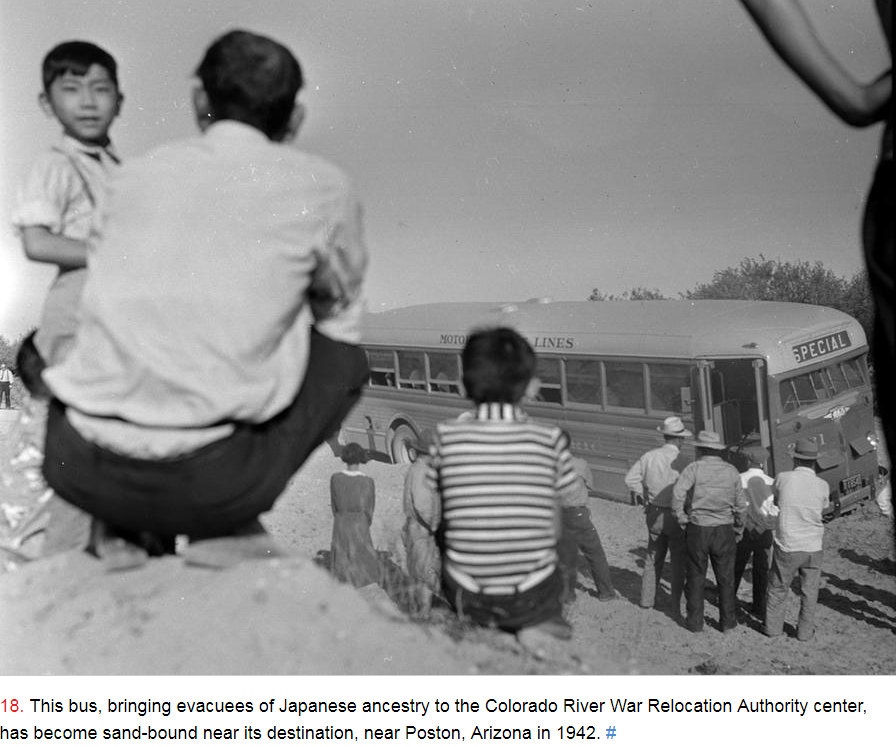

POSTON

(aka Colorado River), Arizona Opened May 8, 1942. Closed November 28, 1945. Peak population 17,814. Origin of prisoners: Southern California, Kern County, Fresno, Monterey Bay Area, Sacramento County, Southern Arizona. 24 Japanese Americans held at Poston later lost their lives in World War II. Poston was divided into three separate camps — I, II, and III.

ROHWER

Arkansas Opened September 18, 1942. Closed November 30, 1945. Peak population 8475. Origin of prisoners: Los Angeles and Stockton.

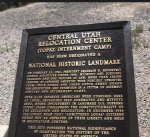

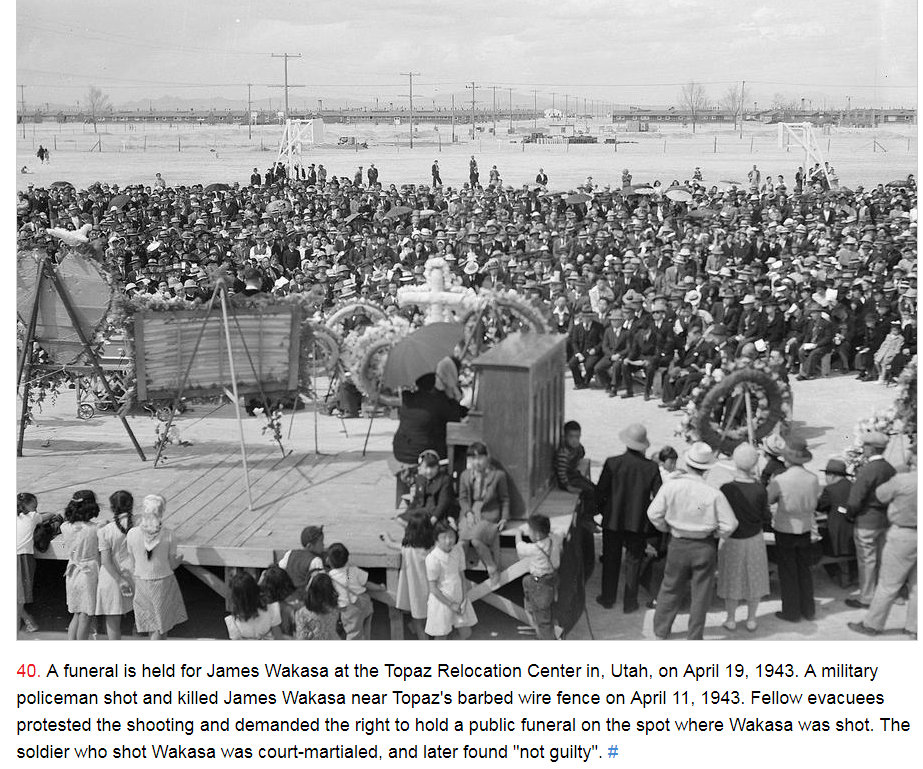

TOPAZ

(aka Central Utah), Utah Opened September 11, 1942. Closed October 31, 1945. Peak population 8130. Origin of prisoners: San Francisco Bay Area.

TULE LAKE

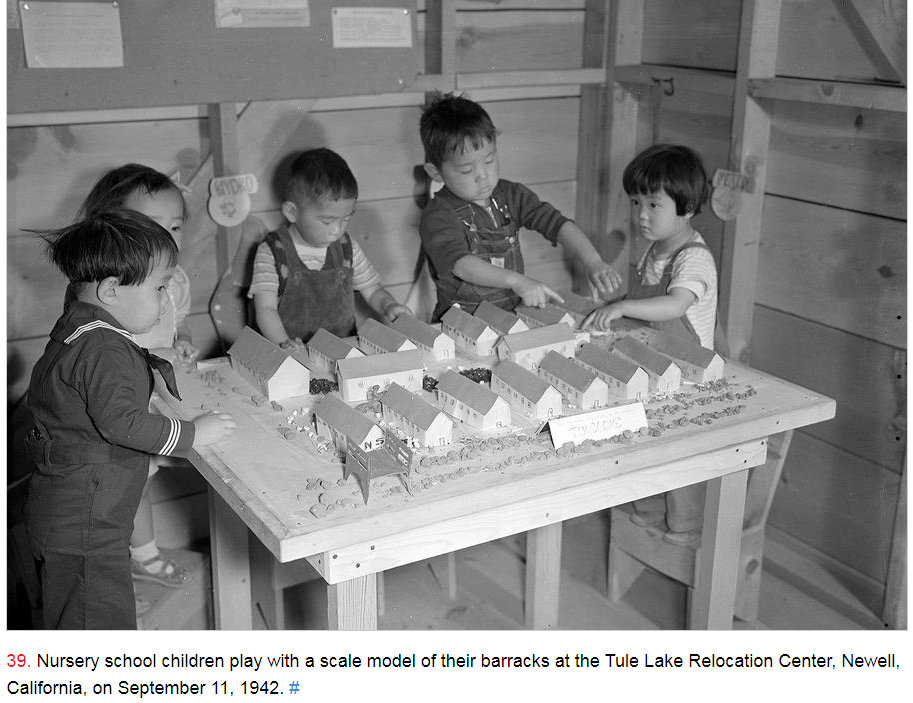

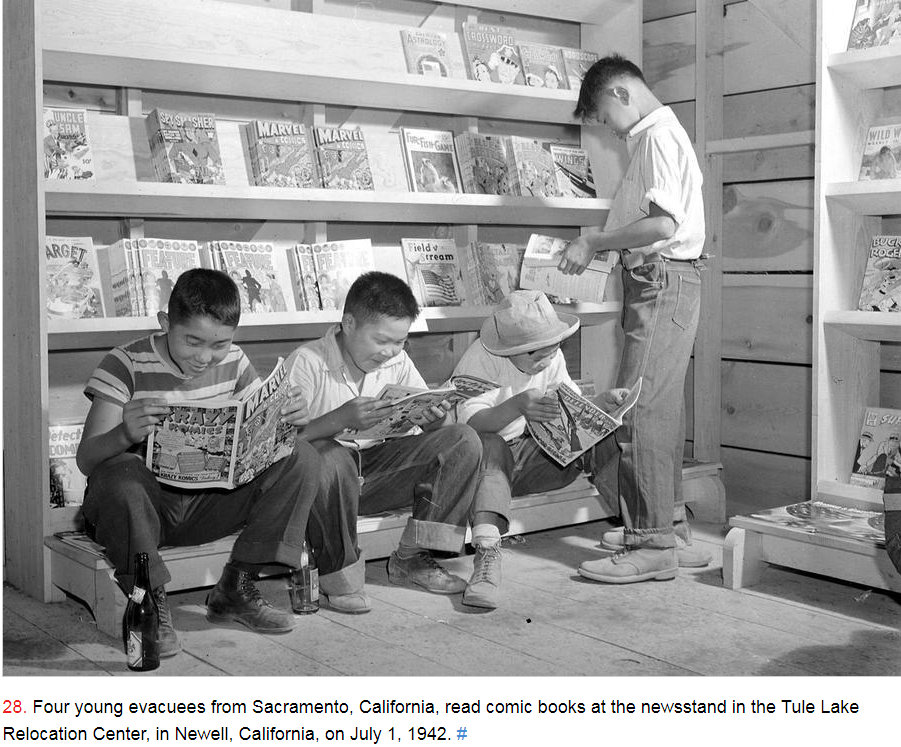

California Opened May 27, 1942. Closed March 20, 1946. Peak population 18,789. Origin of prisoners: Sacramento area, Southwestern Oregon, and Western Washington; later, segregated internees were brought in from all West Coast states and Hawaii. One of the most turbulent camps — prisoners held frequent protest demonstrations and strikes.

TEMPORARY DETENTION CENTERS

Temporary detention centers were used from late March, 1942 until mid-October, 1942, when internees were moved to the ten more permanent internment prisons. These temporary sites were mainly located on large fairgrounds or race tracks in visible and public locations. It would be impossible for local populace to say that they were unaware of the removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans.

FRESNO, California First inmate arrival May 6, 1942. Last inmate departure October 30, 1942. Peak population 5120.

MANZANAR, California First inmate arrival March 21, 1942. Peak population (before June 1, 1942) 9666. Before it was leased from the City of Los Angeles, Manzanar was once ranch and farm land until it reverted to desert conditions. Manzanar was transfered from the WCCA to WRA on June 1, 1942, and converted into a “relocation camp.”

MARYSVILLE, California First inmate arrival May 8, 1942. Last inmate departure June 29, 1942. Peak population 2451.

MAYER, Arizona First inmate arrival May 7, 1942. Last inmate departure June 2, 1942. Peak population 245. Mayer was a camp abaondoned by the Civilian Conservation Corp.

MERCED, California First inmate arrival May 6, 1942. Last inmate departure September 15, 1942. Peak population 4508.

PINEDALE, California First inmate arrival May 7, 1942. Last inmate departure July 23, 1942. Peak population 4792. Pinedale was the previous site of a mill.

POMONA, California First inmate arrival May 7, 1942. Last inmate departure August 24, 1942. Peak population 5434.

PORTLAND, Oregon First inmate arrival May 2, 1942. Last inmate departure September 10, 1942. Peak population 3676. Portland used the Pacific International Live Stock Exposition Facilities to hold detainees.

PUYALLUP, Washington First inmate arrival April 28, 1942. Last inmate departure September 12, 1942. Peak population 7390.5

SACRAMENTO, California First inmate arrival May 6, 1942. Last inmate departure June 26, 1942. Peak population 4739. Sacramento used a former migrant camp.

SALINAS, California First inmate arrival April 27, 1942. Last inmate departure July 4, 1942. Peak population 3594.

SANTA ANITA, California First inmate arrival March 27, 1942. Last inmate departure October 27, 1942. Peak population 18,719.

STOCKTON, California First inmate arrival May 10, 1942. Last inmate departure October 17, 1942. Peak population 4271.

TANFORAN, San Bruno, California First inmate arrival April 28, 1942. Last inmate departure October 13, 1942. Peak population 7816. Tanforan is now a large shopping mall by the same name.

TULARE, California First inmate arrival April 20, 1942. Last inmate departure September 4, 1942. Peak population 4978.

TURLOCK, Byron, California First inmate arrival April 30, 1942. Last inmate departure August 12, 1942. Peak population 3662.

JUSTICE DEPARTMENT INTERNMENT CAMPS

27 U.S. Department of Justice Camps (most at Crystal City, Texas, but also Seagoville, Texas; Kooskia, Idaho; Santa Fe, NM; and Ft. Missoula, Montana) were used to incarcerate 2,260 “dangerous persons” of Japanese ancestry taken from 12 Latin American countries by the US State and Justice Departments. Approximately 1,800 were Japanese Peruvians. The U.S. government wanted them as bargaining chips for potential hostage exchanges with Japan, and actually did use. After the war, 1400 were prevented from returning to their former country, Peru. Over 900 Japanese Peruvians were deported to Japan. 300 fought it in the courts and were allowed to settle in Seabrook, NJ. Efforts to bring justice to the Japanese Peruvians are still active; for information contact Grace Shimizu, 510-528-7288.

SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO

BISMARCK, NORTH DAKOTA

CRYSTAL CITY, TEXAS

MISSOULA, MONTANA

SEAGOVILLE, TEXAS

KOOSKIA, IDAHO

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES AND CITATIONS:

5 Attacks on U.S. Soil During World War

http://www.history.com/news/history-lists/5-attacks-on-u-s-soil-during-world-war-ii

Second Generation Japanese Americans (Nisei) before WWII

http://picturethis.museumca.org/timeline/depression-era-1930s/second-generation-japanese-americans-nisei-wwii/info

When the Japanese Attacked Santa Barbara (1940s)

http://picturethis.museumca.org/timeline/depression-era-1930s/second-generation-japanese-americans-nisei-wwii/info

Remembering The Manzanar Riot

https://densho.org/remembering-manzanar-riot/

List of Detention Camps, Temporary Detention Centers, and Department of Justice Internment Camps

http://www.momomedia.com/CLPEF/camps.html

ADDITIONAL READING

Life after Manzanar

https://heydaybooks.com/book/life-after-manzanar/#

It Can Happen Here: The 75th Anniversary Of The Japanese Internment (Part I)

by Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor of Law, The University of Chicago

Tracing the history of one of the most unconscionable tragedies in American history.

FAMILY STRUGGLES TO SAVE PIECE OF JAPANESE AMERICAN HISTORY

Four Japanese-American sisters are weeks away from losing a home that’s been in their family for nearly a century. The Yuge family has lived in the gardener’s cottage on the former Scripps estate in Altadena since the 1920s, when the late patriarch Takeo Yuge became a caretaker for the property. Although the Yuge family was sent away to a Japanese Internment Camp during WWII, all of their belongings were kept safe in the main house. CONTINUE READING

https://www.pasadenastarnews.com/2015/05/10/family-struggles-to-save-piece-of-japanese-american-history/

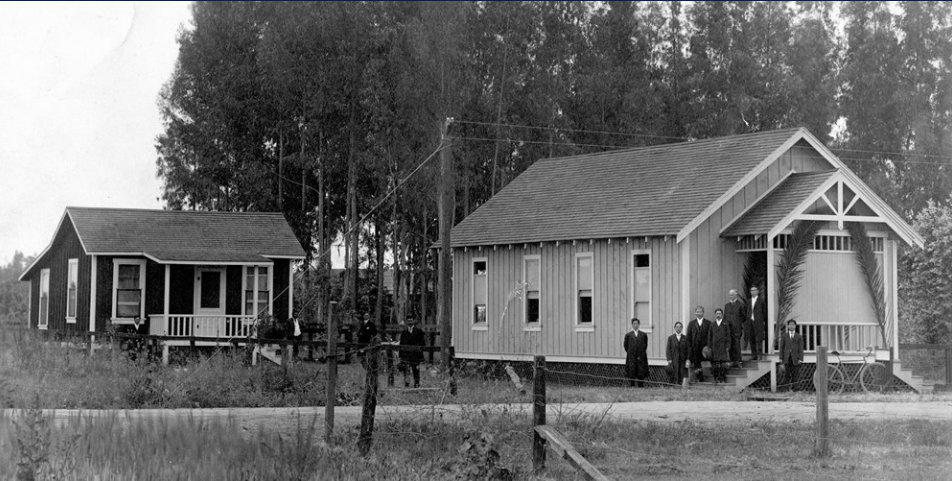

Wintersburg Village — as the property was originally known — once contained churches, residential homes, farmland, and goldfish ponds used to grow fish that were sold to drugstore pet departments. It was also one of few sites owned by Japanese Americans before the California Alien Land Law of 1913, which prohibited people of Japanese descent from owning property. Today, six buildings still stand intact.

CONTINUE READING https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/activists-seek-preserve-historic-japanese-american-site-involved-possible-sale-n858676

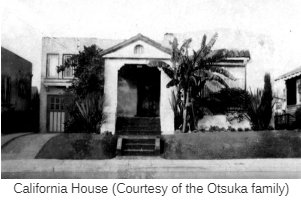

When the Emperor Was Divine

After the war, the family is permitted to return home. But they return to a neighborhood neither familiar nor hospitable. Their home has been vandalized, their neighbors are at best aloof or at worst hostile, and their sense of place in America is forever changed. Though the novel, “When the Emperor Was Divine” tells a powerful story of the fear and racism leading to exile and alienation, Otsuka weaves a compelling narrative full of life, depth, and character. When the Emperor Was Divine not only invites readers to consider the troubling moral and civic questions that emerge from this period in American history but also offers a tale that is both incredibly poignant and fully human. CONTINUE READING https://www.arts.gov/national-initiatives/nea-big-read/when-the-emperor-was-divine

Kristeen Irigoyen-Hernandez

Researcher/Chronological Archivist/Writer and member in good standing with the Constitution First Amendment Press Association

(CFAPA.org)